Tanya Talaga has been speaking truth to power for over twenty years. It is difficult to picture the landscape of Truth and Reconciliation in Canada without her sure voice. Her career of twenty years at the Toronto Star moulded Tanya into the journalist she is today, one that asks the most urgent questions. “Seven Fallen Feathers,” her first book in 2017 investigated the deaths of seven Indigenous high school students in Thunder Bay, Ontario. The follow up, “All Our Relations” looked at the suicide and intergenerational trauma in Indigenous youths. She has been honored with multiple awards including the RBC Taylor Prize and the Shaughnessy Cohen Prize, two honorary degrees and appeared at the Junos. In 2021, Tanya produced “Spirit to Soar” a documentary about Indigenous youth in Thunder Bay, which premiered at Hot Docs. In short, when Tanya talks, Canada listens.

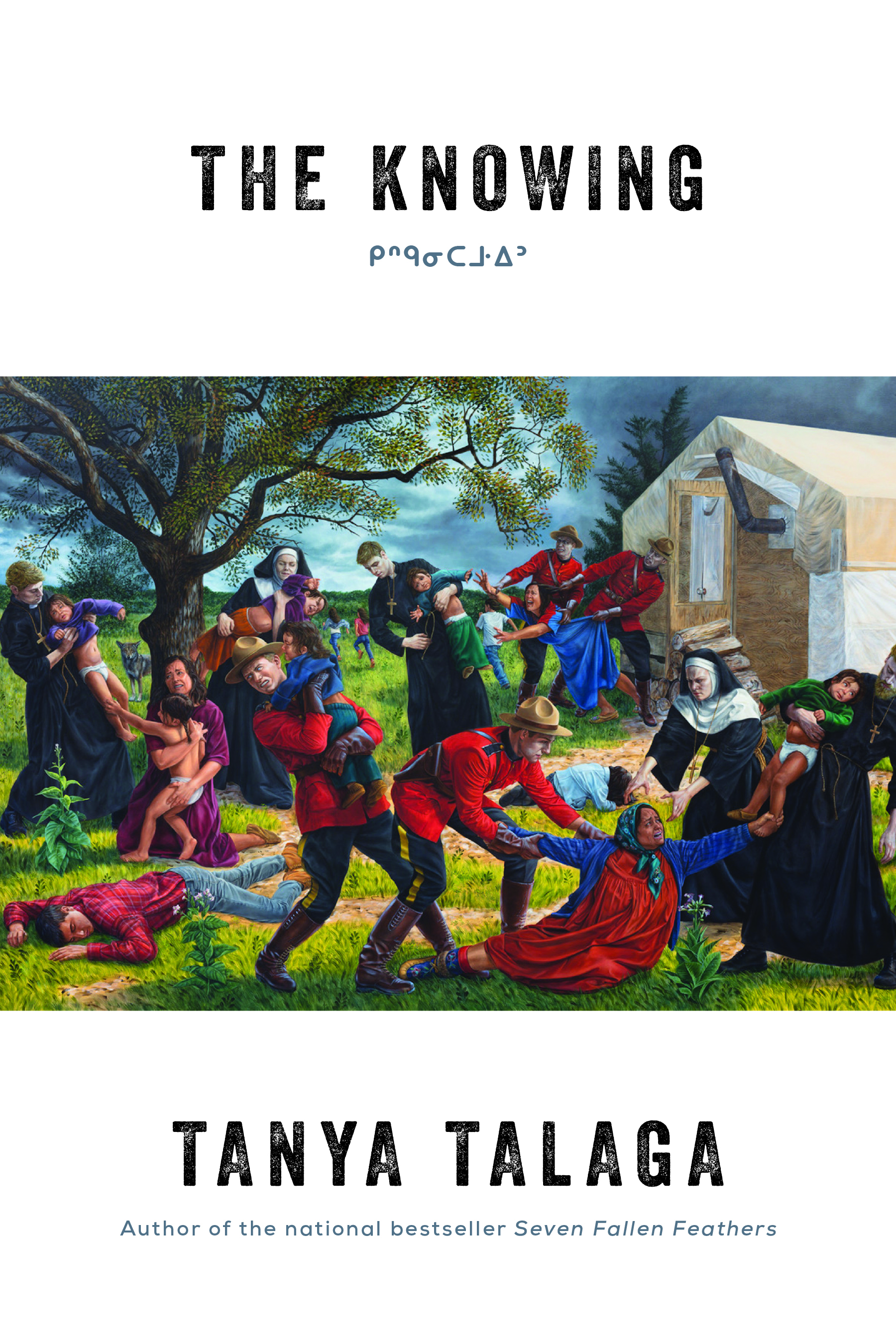

Tanya’s latest book of non-fiction, “The Knowing,” was released in the early days of September and within a week it was already at the top of the Toronto Star’s Bestseller Lists. Along with the book, she has also produced a documentary series of the same name which is streaming on CBC Gem. “I knew that some people would read the book and people would prefer to watch the documentary series,” she says of the decision to release the two formats. “Educationally speaking, it was really important for me. It was important to capture the stories of survivors. To record them and to keep them safe.”

“The Knowing” tells the story of Tanya’s search for Annie Carpenter, her great-great grandmother. The project has been in the making for three years but Tanya’s family has been looking for answers for over eighty years. “My Uncle Hank was doing the searching. He is my great uncle and Annie’s grandson. He was a veteran of World War II and a member of Fort William First Nation. He was trying to find information about his grandmother, his mother, and ostensibly, about himself,” says Tanya. “He wanted to know why his mother was so silent. Why she never talked about who she was, where she was from. Why she refused to speak her language. Why she hated being an “Indian.” When Hank passed away thirteen years ago he handed Tanya a filing folder that held his findings. With it Tanya set out to figure out who Annie was because her mother asked her to. She too wanted to know where her great-grandmother was.

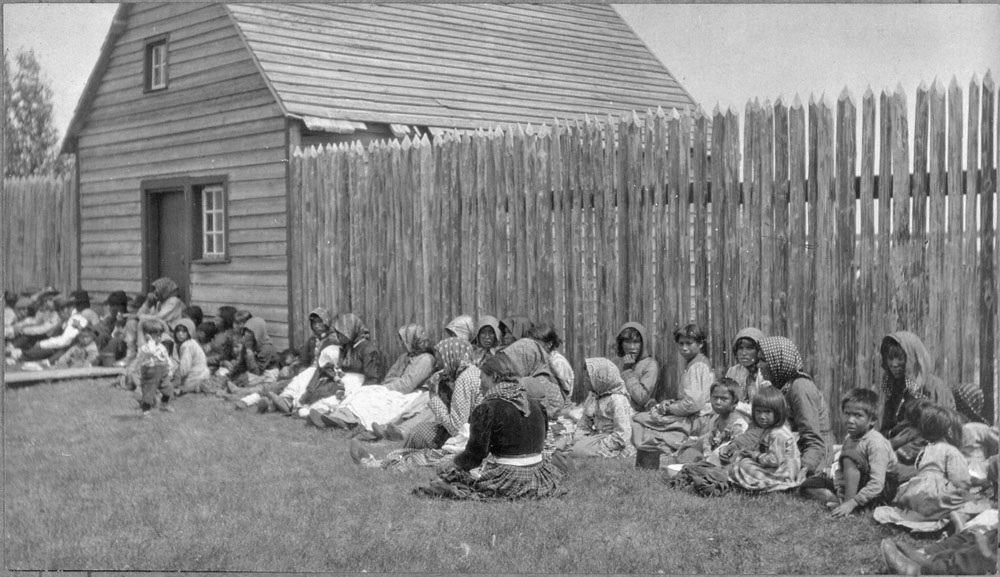

The book opens with the discovery of Annie’s gravesite off of the Gardiner Expressway. A highway Tanya has driven on all her life to get to the Sherway Garden mall. To get to Ikea. Annie had been all around Tanya all this time and she had never known. Tanya reflects on the shocking revelation. “You know, as First Nations peoples, we’ve all heard stories of people that disappeared. Either in Indian residential schools, in Indian hospitals, in asylums, in tuberculosis sanitaria. People just disappeared. We all know folks in our communities who didn’t come home,” she says. “With the passage of time, memories dim. The finding of the Le Estcwicwe̓y̓ – the Missing in Kamloops, the potential graves of 215 children, and the missing of our own families; if you’re a First Nations person, it’s all the same story.”

Tanya has written extensively about and reported on the effects of colonization. On the racist policies of the Canadian government that set up the Indian Act, Indian residential schools, and the reserve system. In “The Knowing,” she brings our attention to the effects of all these elements on families. “This is just my family’s story and I’m just one person,” she says, “every single First Nations person has a similar story. Every time I found something really big I would let my cousins know in our email thread.” One story in particular was hard to share, that of Thomas and Samuel Skelliter. “We found out that they were buried at Shingwauk Indian residential school. We didn’t even know they existed. They were my great-grandfather’s older brothers. I had to tell the family about these two boys. There was a weight to that. It was hard.”

We talk about the Papal apology chapter in the book, an apology for which a First Nations delegation traveled to Rome. Three years on, the needle has not moved far on educating Canadians on Indigenous history, considering residential school deniers express themselves freely everywhere. “We have a long way to go,” Tanya says. “Specific to the Catholic Church, so much more could be done. Where are our records? They’re still at the Vatican. Why aren’t they here? Why do they have to hold on to them? Why are our things in the Anima Mundi Ethnological Museum? Why haven’t they been returned to Canada? What is taking so long for that to happen? Why hasn’t the Catholic Church paid the $25 million they owe to the residential school survivors from the agreements in 2007 and 2008? Where is that money?”

The Canadian Government too has not made the progress it had so spiritedly promised. Only 13 of the 94 Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), in 2015, have been completed. A woeful number. A report by the Yellowhead Institution states that from January to September of 2023 no Calls to Action were completed. Eight years ago, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised to implement all 94 Calls to Action. The promise remains unfulfilled. Canada supported a motion by Leah Gazan, Winnipeg centre NDP Member of Parliament, to officially acknowledge that a genocide occurred in the country, “yet we’re still fighting to make denialism a hate crime. Because it is,” she says. “There are people who say, show us the bodies. Why would a community that has been grieving and been under the spotlight accept such demands? The denialists – they’ve got websites, they’ve got books, they’re speaking out publicly on social media. It’s ridiculous. I think that the Governments of Canada and of all the provinces should be stepping up to make sure that denialism is a crime.”

Writing about Indigenous history in Canada is essential and necessary. Tanya has dedicated her career to it. We wonder how she takes care of herself when faced with stories of grief and violence endured by Indigenous communities, both in the past and in present day. The answer, she says, lies in community itself. She tells us about a dream she had about the Anishinaabe Midewiwin, the Anishinaabe Medicine Wheel, when she was thinking about the structure of the book. The Wheel shows the four stages of life and how everything is a circle. An end is a beginning. “I was talking to Elder Sam Achneepineskum about this. We were in ceremony in the sweat lodge and when we came out, I spoke to Sam and a few other Elders about using the concept of the Wheel. We had a massive discussion and everyone said, yeah, you should do it. So that’s where it came from.”

Community is what keeps Tanya going. She attends ceremonies whenever she can and she is a part of many Indigenous communities. “When I’m writing I get sucked in a vortex trying to find out all the information I possibly can. I get obsessed!” she says. She admits she isn’t healthiest in those periods. That she should walk away from her desk more. Sleep more. “I wish I could tell you that I was doing self-care and yoga. But that’s not true,” she says. “There’s also no fantasy of a cabin in Banff where you go and sit on a mountain and write forever. We have jobs, we have lives, we have children. Someone’s got to do the laundry and the cooking and everything else. But all that also keeps me sane. Going for a run with my dog. That keeps me sane!”

When asked about her writing influences she talks about Lee Maracle who was also a friend. Specifically her book of fiction “Celia’s Song.” Thomas King’s “An Inconvenient Indian” and his Massey Lecture, “The Truth About Story” Angela Davis’s work and Richard Waghamese. All works she rereads often. Tanya’s courage to speak her mind has set her apart as a journalist, a writer, and a thinker. “I firmly believe that my ancestors, speaking as an Anishinaabekwe, are with me and they help me very much. The voice that sits in your head that tells you ‘do this, do that, turn left, don’t turn right’, I always listen to that voice. The moment you stop listening to that voice, is the moment you start to go astray, as a writer, as a thinker.” We talk about how it’s not easy for up and coming writers and journalists who are working and learning in mass media and institutions with colonial roots. And for Indigenous artists especially, who are managing the grief of their personal histories at the same time. It’s not easy. “It’s not easy,” she agrees, “but you have to earn a living. You have to try. You have to try and change what’s not working around you and that’s not easy to do. And for Indigenous peoples too. Our writings come from so many different sources, from oral history, from our elders. We must stay true to that.”

Looking back at the early days of her journalism career, she is struck by how different the landscape is now. She remembers the words “Native” and “Aboriginal” being used in headlines. “There was no context for Indigenous stories. People didn’t talk about the Indian Act and about Indian residential schools. It was such a different time.” She is still hopeful about how many different ways there are to publish writing and to get Indigenous stories out into the world, through indie presses and websites. She started her own production company so that she could be in charge of her own newsroom. But that didn’t come overnight. “A journalist’s role is to tell the truth,” she says, “to find the facts. To publish the facts. But that’s hard because you can’t do it alone. If you’re a journalist, even if you’re an editor, you’re not in control of the newspaper, you’re not in control of the news channel.” Even as we have this conversation, debates stir around us about the inadequate media coverage of multiple genocides occurring in the world, and of the burgeoning climate crisis. In a sense, this moment feels like something out of Canada’s past. A rerun. It’s hard not to feel powerless in these turbulent times.

Tanya still has hope. “Don’t give up,” she says “just don’t! If you give up then they’ve won. Keep moving towards the truth. Eventually it will come. But for lots of people, we’ve lived entire lives like this, without access to the truth. The truth has taken a long time to surface. But it eventually does. You just have to stay the course.” We talk about the role of settlers, especially new immigrants in the truth and reconciliation process. “We all have a responsibility,” Tanya says. “Murray Sinclair says it all the time: teachers and education got us into this mess and teachers and education will get us out of it. We need changes to curriculum so that the next generation of lawyers and doctors and editors and journalists know the truth about this country. If people were to read the TRC, take even one of the 94 Calls to Action and apply it to their lives, I think we could change Canada for the better.”

The education system will no doubt be a key component of achieving justice for Indigenous communities. But it’s not hard to see why Indigenous Elders and even youth would view education with distrust. Education systems need to take these sentiments into account. As it is, the infrastructure and support systems for Indigenous communities are sorely lacking, let alone resources and grants to support emerging Indigenous writers and artists. “A lot of our children don’t have high schools in their communities. I can speak for Northern Ontario and we don’t have high schools. We’re still sending our children to Sioux Lookout, to Thunder Bay, or to Timmons if they want a high school education. So regardless of grants to be a writer, we need basic equity and human rights. I would always say: we need more.”

There seems to be a tendency in Canada to want to move past its violent genocidal past as fast as possible. But sitting with the individual stories of survivors and engaging with their grief and trauma is what will bring about meaningful change. To really sit with these stories, and letting them move us. Not land acknowledgments, and not one federal statutory holiday. “The Knowing” helps us do exactly that. It brings us into the hearts and minds of Annie Carpenter’s family members. In its singularity it holds the door to understanding the past, present, and futures of Indigenous people.

Tanya Talaga is appearing at Vancouver Writers Fest this week. “The Knowing” is available in bookstores and is streaming on CBC Gem. The TRC can be accessed here.

– Prachi Kamble (Twitter), Annapoorna Shruthi (Instagram), and Amrit Sanghera (Instagram)