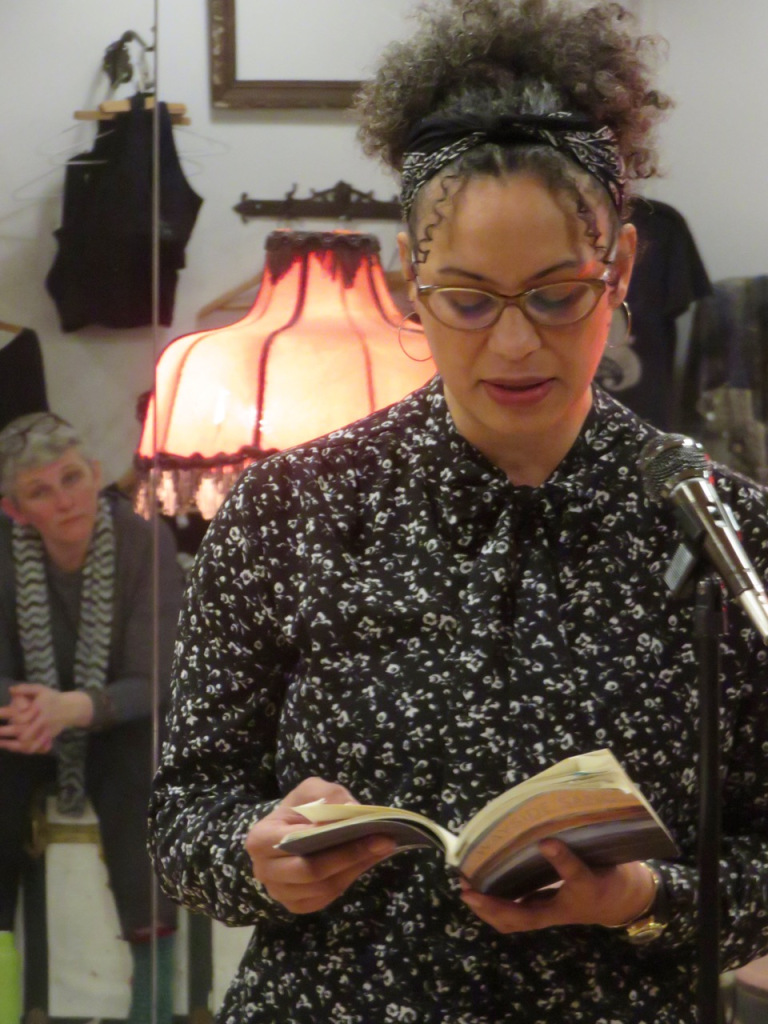

Cecily Nicholson won the 2018 Governor General’s Award for English-language poetry for her latest book, “Wayside Sang”. She has two other books of poetry called “Triage” (2011) and “From the Poplars” (2014).

“Wayside Sang” concerns entwined migrations of Black-other diaspora coming to terms with fossil-fuel psyches in times of trauma and movement. This study is, in part, a matter of strengthening relations and being situated despite displacement. It is an effort to be relevant at a time of rebellion as Black networks, community, and aesthetics gain new qualities. The work is attentive to, entwined with, and influenced by, Indigenous resurgence and poetics. It looks to Anishinaabeg, Haudenosaunee, and Attawandaron presence and histories – to Indigenous memory as a constant to land, as constitutive elements of Nicholson’s poetic practice.

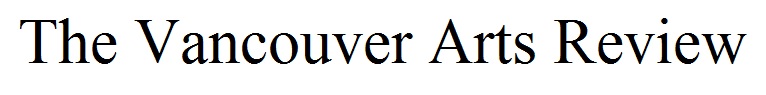

She was generous enough to sit down with us, Bethany and Maira, in a busy café to discuss her work, gratitude, and making space.

If you’d like to hear Cecily read her poetry, you can follow her Facebook page entitled “Cecily Nicholson.”

The transcript below has been edited for clarity and length.

B: Can you tell us about writing “Wayside Sang”?

I set out, in part, to try to connect to the narrative of my birth father. This is someone I never knew but connects me to my ancestry and the experience of being part of the black diaspora in North America. He travelled: he crossed the US-Canadian borders in a number of places but especially in the Windsor-Detroit area so I also set out to focus on a study of that area – thinking in particular of the Great Lakes regions, of the Indigenous territories in that area, of my own journey. I grew up not far from there, to the Pacific coast, and the many roads that I’ve taken back that way.

But in the absence of really knowing much about my birth father I ended up taking a step back and thinking about the kind of life that might have accompanied somebody like him. Thinking about their relationship to the roadway, to travel, and then picking up the metaphor and analogy of the automobile and the automobile industry. And in the long run, I ended up writing more and more about, and thinking through a lens of, a shifting landscape and climate and trying to connect back to my own relationship to the car as a place of comfort, escape, but also entrenched – in the book I talk about fossil fuel psyche – in the ways which our lives are so entrenched in car culture and contemplating what a future might look like post-fossil fuels when that’s so fundamental to how we think. So a lot of threads got pulled as I was trying to think through, in a core sense, a notion of ancestry and being black in this landscape.

M: Can you tell us about shifting political landscape relative to art, in particular to Vancouver at this moment right now?

I think it’s critical. It feels more important to me and certainly in recent years, I have shifted my life to work more and more in concert with the arts even as I come from a very applied and frontline social service background. But I could see, even years ago, just what it meant for different communities, particularly working with the Downtown Eastside. We need to live, we need to survive, to be resilient – but we need reasons, and culture, in a grounded and relational sense, is really critical to that.

Fairly safe to say that representing my own poetics and my presence in Vancouver has at times had its challenges. But I’ve always, as long as I’ve been a poet in the public sense, I have had a community. I’m really grateful for that. Even as I can point to significant problems in terms of representation, still very pervasive situations of anti-blackness that occur in this town, that I’ve still managed to find support and community and interest in an audience. I feel very grateful for that but also feel that it’s really integral that part of that work is to give back to that audience and to help reconnect and build connections with new writers or established writers who perhaps we should know more about.

B: That leads into one of our other questions about what advice would you give youth who want to go into writing, especially women or people of colour?

One of the things I would say right away when I’m talking to somebody who’s looking for advice or is interested or open to advice about how to be a writer is that, first of all, you need to practise. Not unlike the painter, not unlike the athlete, we have to practise. Part of the way that we practise is in relationship to other people. I think it’s really integral to find community and find places and ways to express and to share that. Starting out it’s nice to find nurturing environments where people have thoughtful and compassionate listening ears. But also, sometimes it means stepping into challenging positions that make us feel really nervous and really feeling strength in that. Sometimes when we’re the most nervous is exactly when we should be speaking. I would emphasize whole-heartedly the notion of community and the notion of practise.

The other thing I would say about being a writer, being an artist, personally to me: it’s about being a whole person and to do other things. To be involved with community, involved with other practises, to be a listener, to be a reader. I have never been able to set out to just be a writer. I think that what makes writing interesting is that you actually have purpose and goals that are beyond that of just being a writer.

M: When you talk about space, making that space, wanting to practise, how challenging can it be to find those kinds of spaces and nurturing environments? I was wondering if you had something to say with the communities that you were involved in, what has been nurturing in Vancouver or being near the Great Lakes?

A lot of things. Straight up, I would say a lot of wonderful other poets in my life that are my friends and my community. We’re everywhere. Or other artists who are interested in collaborating with the written word. So I’ve always had that. I’ve always looked to some really wonderful figures on this landscape, like Rita Wong for example. I think of some of the singular work, someone like Wade Compton.

I’ve had a lot of wonderful influences, from the SFU English Department in particular through the years. Most recently as the writer-in-residence there, but my relationship to the community of poets who connect through that space has existed from before that. I don’t know if you recall Rhizome Café that existed for a period of time on Broadway. It closed down. The rent, just like everywhere, went up extraordinarily. But it was a very community-based, social justice-based café that supported a number of different struggles – working communities, migrant justice work, there’s a long list. They would also host a lot of gatherings. So for a period of time around 2010 through to when they closed, we had a ton of great readings there. They were these super friendly spaces, kid-friendly so there would be children. There would always be food. So those are the kinds of accesses – physical access as well as a friendly place to be – that describe some of my early influences.

B: Have you found, as affordability has become a bigger issue in Metro Vancouver, that it’s affected the arts community?

It’s affected everyone. But I think more critically from the vantage of the downtown core, I think it’s to the detriment of people’s well-being and health and survival. I wouldn’t want to dwell too much on how it’s affected me. I’ve been evicted twice in the lower mainland, personally, however I move with a great deal of privilege. I feel like, as a renter, I’m not a property owner, it’s made it difficult for a lot of us.

And I think it also makes it difficult for how people spend their time. So when we’re concerned about income, when we’re concerned about improving our status, to what extent does being a poet assist with that? For most of us, it’s not really a benefit. It might be – at this level for me it certainly is – but there isn’t a huge gain, certainly financially, from that.

When I think of the downtown eastside community, it has informally, per capita, and, anecdotally I can say, a huge proportion of artists in that community. But those are artists who are not publishing or not necessarily exhibiting, who may not be creating permanent works for publication that you can read ten years down the road. They’re not gaining artists fees, they’re not getting an honourary to read. They’re carving, they’re sitting on a curb to do so, they don’t have a studio. I feel like, for those artists, absolutely, the city is pushing them out. It already has for many folks.

B: Where do you like to write? What sort of atmosphere do you like to create?

M: Paint us a picture.

I write alone. I’m not someone who can sit in a coffee shop and focus. I typically write in my home space. Sometimes, if I have an office I may have worked there. Generally, I have a good corner on the couch or a good chair. I am always working on a laptop or with handwritten notes.

I guess it depends on how you define writing. If we’re thinking about a finished or almost finished poem, I would be on a computer and I would have to be there. But for me writing is a long thread of things. There are the notes that you take, your observations, your ideas. Maybe those churn through and get written more than once. They get transcribed. Maybe a poem gets written, but then I’m also editing. Editing is a big part of writing for me. It’s actually one of my favourite parts of it. I’ll revisit and study my work over a period of time.

B: How do you know when a poem is done?

I once was asked that in an interview and I joked that you know the poem is done because the book is due. You have to turn it over. Sincerely, it’s a good thing to publish, personally for me, because otherwise I would keep editing.

The poem is done when it’s hit the page in a permanent form and I no longer have the power to edit it. Poetry feels to me like a live document. It’s something that can continue to grow long after it crystalizes.

That said, another marker of where I feel like I’m ready to let it go is at a point when I feel like I can read it out loud. It has translated from what I’ve written into the orality. I’ve reached a point where whatever I’ve set out to try to do on the page has made sense enough that I can now read the poem and speak the poem. In the early stages, I can’t do that with work. So I think that matters.

– Bethany Dobson and Maira Hassan