I would like to acknowledge that Vancouver is on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Musqueam, Squamish,and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations- Maddison Miller

“Sandra Semchuk’s work reminds us of the necessity to continually rethink our positions as artists, as speaking subjects, as listeners.” – Althea Thauberger, artist (nominator for the Governor General 2018 Award)

On March 30th, 2018 I had the privilege of interviewing Sandra Semchuk in recognition of her receiving the Governor Generals Award in Visual and Media Arts in Ottawa on March 28th at Rideau Hall. Sandra Semchuk is a Ukrainian-Canadian photographer based out of Vancouver, Canada, and an artist of an autobiographical nature. Semchuk uses photography as a tool to become witness, observer and visual participator of the spontaneous episodes and changes occurring within nature and her surrounding friends and family. Her works emphasize the ongoing and personal investigation into the human process of denial, identity, love, reconciliation or conciliation, nature, the human world and the wider than human world. Sandra Semchuk’s works, along with the additional seven artists who also won the Governor General Visual and Media Arts Award, were exhibited at the National Gallery of Canada on March 29th 2018. The following, is a transcribed phone interview I had with Sandra while she was in Ottawa after receiving her award.

Hi Sandra, congratulations on receiving the 2018 Governor General Award! How does it feel to be recognized and honoured by the Canada Council for the Arts?

Hello Maddison! Oh it’s really an honor, it’s a very nice thing, a delight. The events were absolutely beautiful. Everyone who organized it had done so well, with such generosity. There was a tremendous warmth from the community.

Can you give us a glimpse into what it was like growing up in Meadow Lake, Saskatchewan during the 1950’s/60’s/70’s?

I was born in 1948, and Meadow Lake was a Northern town between First Nations and the North. I grew up painting animals, cowboys and cowgirls on the windows of the grocery stores all down the main street. I started when I was 7. The townspeople really encouraged me to be an artist. They thought what I was doing was pretty cool. It had such an enormous impact for me, because you know, you love the people in your community.

When did you realize your artistic relationship to photography? What artists inspired and motivated you growing up?

When I went away to University, I ended up doing my Bachelors of Fine Arts. Coming from a small town, I didn’t have much access to what we call “Fine Arts”. What I had access to were books. When I was small, just starting school, they would bring books to Meadow Lake in these green metal boxes. There were books by Rembrandt, his self-portrait work, which I loved so much, and by other artists. And I would really just stare at them, I was that little girl that would just stare at things. When I first went to Saskatoon some of the earliest paintings I saw were Emily Carr’s work. I saw an amazing piece by Emily Carr at the Mendel art gallery and that was very moving.

Do you have artists who inspire and motivate you now?

I do, I do. A lot of the contemporary artists that we have in Canada have been very, very inspiring for me, and a lot of photographers. We are so lucky in Canada to have had a National Film Board Stills Division that helped to distribute photography across the country. They would distribute them in soft shell boxes that went to smaller communities. I was one of the founders of Photographers Gallery in Saskatoon…it’s called Paved Art now. Those artists, which are Sylvia Lisitza, Richard Holden, John and Jo Nansen and others, were really important for me because they had visual conversations. Because we had established the Photographers Gallery we were always bringing in other artists, learning from their work.

I’m just on my way to Montreal and I will see Gabor Szilasi for example, and Doreen Lindsey. They were really important for me at the beginning, and people like Marion

Penner Bancroft and Jayce Salloum from Vancouver, came and exhibited their work.

This visual conversation you talk about, when I’ve been researching your works, a lot of what I’ve found was what you entitled, “a negotiation of identity” between the photographer and that which is being photographed. Can you discuss this “negotiation of identity” and the importance of viewing your artistic works as a collaborative effort?

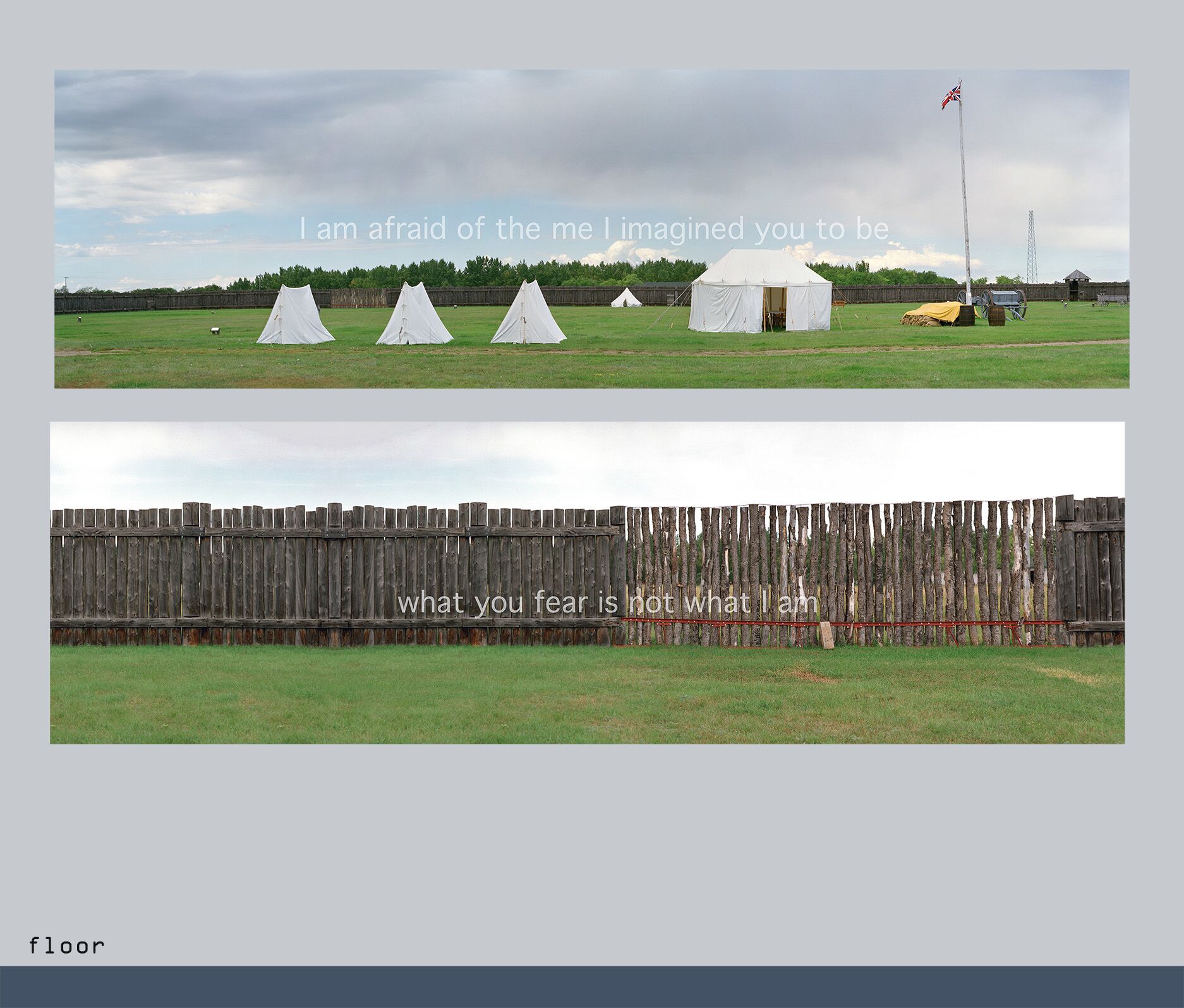

My husband, James Nicholas, was Rock Cree from Nelson House Manitoba. In a sense our marriage was an opportunity to see how those structures of colonization and the structures that were created by residential school were being played out. We were both caught in that history. Me as a Ukrainian-Canadian, and he as a Rock Cree. So what would happen, in daily life there would be these opportunities to bear witness to these things. For example, we had gone to the treaty six gathering of elders in the Loon Lake area, and we were speaking with an elder about generosity. And the elder was talking about how things got turned upside down in Canada, so it was made to seem like the settler people were the generous ones. I remember, when he said that, it’s like you had just gotten punched in the gut. Because, it was so real, like you knew it, you knew that generosity is at the heart of the culture. If you know people who are Cree, or many of the First Nations on the West Coast, that generosity and the give-away for example, are right at the very foundation of the culture. So, that is extraordinarily difficult when someone does not recognize that is who you are. I said to James, “James, would you teach me how to say thank-you for sharing the land in Cree?” and he got mad at me and said, “You don’t understand, sharing is law. The land owns itself.” And that’s how it would go. There would be dialogues, that would penetrate the situation and open up some way. It would appear to be a simple thing on the outside, but as you followed it through, and you thought about it, and made images about it, you started to work together to create text to go with the work. Then, you saw it become something that was important, and vast, and had affected your cultures in profound ways. And always the photographs were taken of the land in some way, you know, that kind of respect for the land.

Do you have tools you use as a photographer to ensure the authenticity of this ‘negotiation’ while it is happening?

I love that question, I think it is a wonderful question, I really do. Do we have tools? Yes, we call it, the Love Stories.

You did an exhibition called Love Stories, didn’t you?

Yes, exactly. That was because, because we cared about each other, we really cared about each other. We tried the best to remain authentic and to drop any kind of projective narrative, you know, that’s a really difficult thing. Often what we call ‘love’ between couples, is projective rather than the actually seeing. You’re trying to see past the structures that we hide behind, or that we’ve taught ourselves. So, we were learning from each other, that’s what love is. It’s an opportunity to learn how to be, how to be with one another, to have that authenticity of presence.

Often the subject matter I’ve witnessed within your work is quite heavy and requires intentional observing as a viewer. Does that affect how you approach your role as a photographer? How do you stay inspired when confronting such important and impactful issues?

We worked together with Pravin Pillay to do a piece called Afraid of What I Could Become. It brought together Pravin’s experience of working with Doctors Without Borders as the first acts were occurring in Rwanda amidst the genocide there. First Pravin speaks, and then James speaks about his personal experience in residential school where he asks the question of himself, “am I complicit in the genocide of my own people,” referring to the lateral violences. And then, I’m in there as witness, listening to these two men speaking, along with the singer Joyce Dancer. We were considering the deep narratives in Saskatchewan around the handing over of small pox blankets, and how when you’re asking the question, how do you keep going, how do you keep your motivation going when you’re put in a situation in which you have to face the truth, something that’s almost impossible to face.

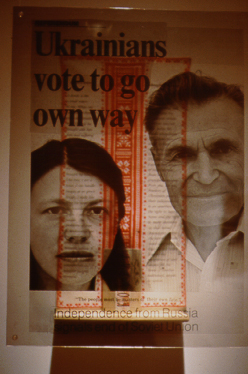

The question for me became, how do we move out of denial of the ways in which, for those of us who are born of what we might call, settler cultures, how do we move out of denial of our ongoing complicity. Especially, if we are not naming it. You are caught between two things. You are caught between the desire not to feel that terrible pain and sorrow and at times guilt and shame; and the recognition that if you don’t speak out, that you are complicit. When we look at any kind of traumatic experience, let’s say the Ukrainians in Canada who were interned in World War One, you are looking at how people don’t tell the stories. That has been the case, for First Nations as well as other Nations. Because these stories aren’t told, the likelihood of them reoccurring is greater. You try to weigh and balance things. You think, maybe the kids won’t suffer so much if the stories are told.

The intergenerational trauma has passed, regardless of whether the story is told or not. There has got to be at some level choice making. The process of what we are calling ‘reconciliation’ or ‘conciliation’ is a process of moving out of denial, which is extraordinarily painful. It’s painful for us as settler peoples, but it’s equally painful for First Nations, at least it was for James. For him, denial also protected him. It’s one stage at a time, and it’s really hard work. But, because we were a generation that was university educated, we were given some skills. I feel we have that responsibility to develop those muscles and skills and knowledge so people don’t have to keep repeating history. In the end, we were really interested in peace.

Keeping with the discussion of the ‘process of denial’, in the short film produced in recognition of your receiving the Governor General Awards, you had talked about how your grandma played an important role in your personal investigation into it. Can you touch on this?

My grandmother loved her children and her grandchildren, nieces and the family members in what I would call an unconditional way. She had this ability to see others, which is very extraordinary. She had a very difficult history. How the lateral violences, of what had happened in the old country Ukraine had affected her both there and here were brutal. She told me the stories, some of them, not all of them. It meant that I carried that pain, we carry it in either case whether the story is told or not, but I carried it the pain more consciously. That is the shift when you become witness to the states of mind that you are going through. As you become witness you understand better and you are more capable of transforming or changing those states of mind and learning more about them and investigating them more.

Do you think that’s maybe one of the reasons you were drawn to the medium of photography because it naturally puts you in the space of being the witness?

Edmund Carpenter talks about how we need some level and degree of distance in order to be able to see, it’s the islander that sees the mainland. He has this wonderful story he tells from John Culkin, “we don’t know who invented water, but we’re damn sure it wasn’t fish” and “if you have saliva in your mouth and you swallow it you can’t see it, but if you take your saliva and spit it in a glass you can see it but can’t swallow it.” So, you’re right about photography. The essential strength and dilemma of photography is that you can be both inside and outside of experience at the same time. Photography gave me that training and discipline of becoming witness, but at the same time I was still wanting to remain within experience, so my practice needed to incorporate that, which is where the performative work came into play. They were the “moving parallel” works.

Would you say, you use the camera gesturally with performance pieces? How has using the camera gesturally contributed to your art practice and technique? You talked about how it created a space which allowed you to traverse the boundary of being ‘the witness”…

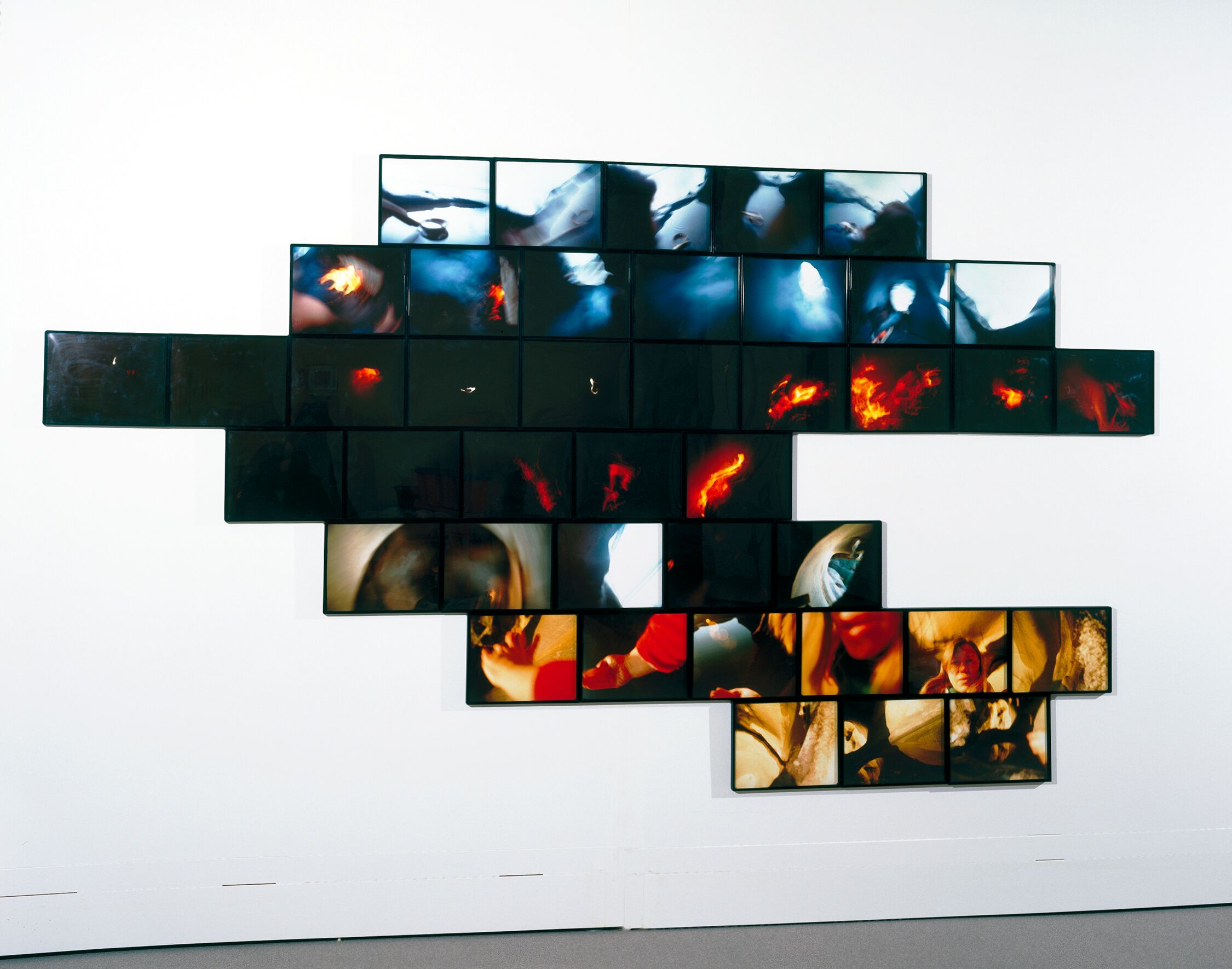

You’re just about there! You almost got it. For example, my daughter Rowenna would do spontaneous performances in nature. She would take green slime and braid it. I remember one time, when she was about seven, we went to Lake Huron which is a very beautiful lake close to London, Ontario. When we got there she took off her shoes, rolled up her pants and ran to the water and yelled with all of her might to the waves, “HEEL!” And of course, the waves knocked her over. Then she went down to the sand dunes, and crawled on her knees in a circle, around and around until she got to the center, then curled up in a little ball and sat silent and still. So these kinds of behaviours articulate what I would call ‘disposition in the moment’, again states of mind and moments.

At that time, I had the opportunity to study with Chin Shek Lam, an important artist in Vancouver. A Chinese artist, who was a master calligrapher and seal maker. From him, I learned that the brushstroke itself is an articulation of ‘disposition in the moment’. You are being totally present in the moment as you are making the stroke. All that complexity of the teaching of the stroke is within you. This is all in relation to the wider than human world. Because I did that work so much- he had me doing 100 strokes a day- eventually, it became incorporated into me, and I began to use the camera gesturally. Playing it much more like a musical instrument, not looking through my eyes, trying to find ways so that the whole body is a part of this negotiation as I move parallel to what I was seeing as these spontaneous rituals that are being enacted.

I think that work was key because it had so much to do with synchronicity and simultaneity because all of those images were coming together to form one piece. This was not an appropriation of reality, but another way, a glimpse, a more peripheral way, perhaps it was more the forces you were engaged in as you negotiated the mutual dance with one another.

So would you say using the camera gesturally and creating story-boards out of your photographs evolved simultaneously? At the same time?

Yeah it did. You’re talking about sequencing, right?

Yes, sequencing!

Yes, it did, it did.

Do you feel you’ve accomplished or experienced what you may have set out to initially do at the start of your artistic career? Or do you find its constantly evolving?

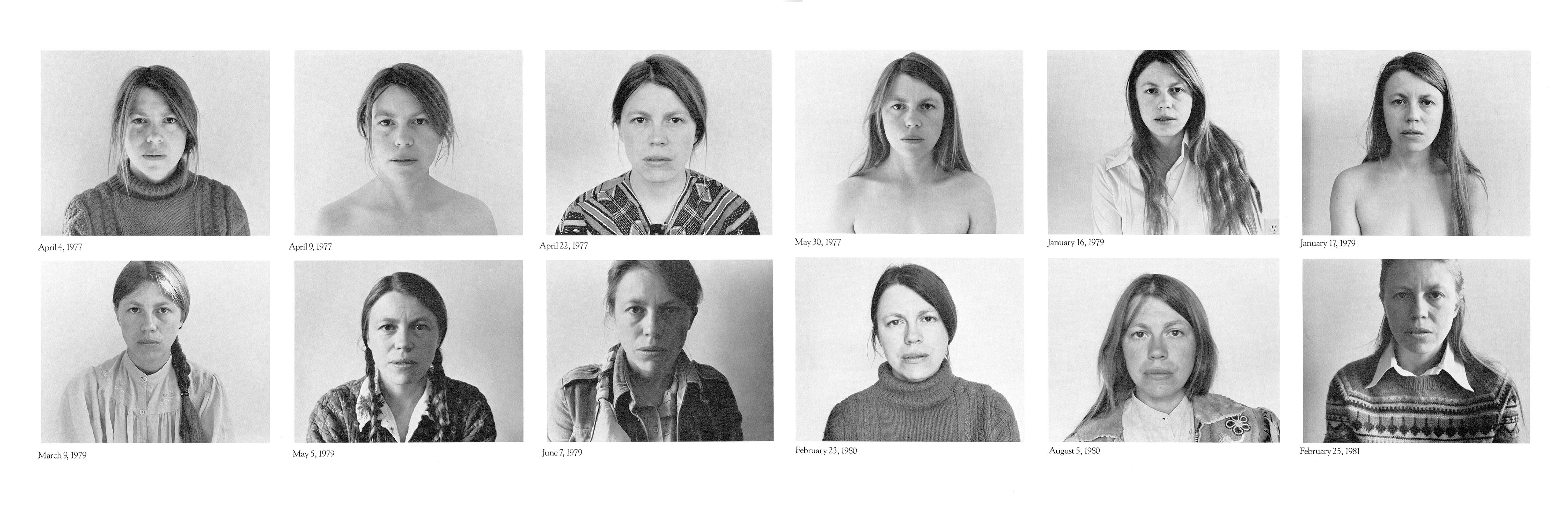

When I began my work, there was a sense of “you don’t know what you’re doing,” and I didn’t. But when I began my autobiographical work, my question was, “how do we change?” This question came from real concern. Remember, we are looking at the early 1970’s, and we’ve just been through a student revolution, and people being very critical of what was happening, particularly in terms of resource development. And, you’re looking at it as a kind of violence, right. People were not taking responsibility for the violence that was being created. I wanted to know how change occurred, so I decided to use myself. That’s when I would go before the camera. When I felt something strongly I would use the shutter. I could feel myself moving and changing, the kind of ridiculous things that artists do that are almost invisible and very difficult to ever catch. But there was this investigation into states of mind and the shifting and the changing states of mind.

I had curiosity about states of mind and presence and quality of presence as being glimpses of where change might be occurring or capable of occurring. I don’t know why that happens, but it’s like a glimpse of something you’re pursuing. It’s like a thread. You pursue it this way or pursue it that way, but it’s the knowing that there is something which happens when dialogue occurs between you and the wider than human world in which something is enlivening. Something engages you in a compassionate and loving way which pulls you forward. James would call that pimâtisiwin, life itself is the most important thing, and using that as a measure for right actions.

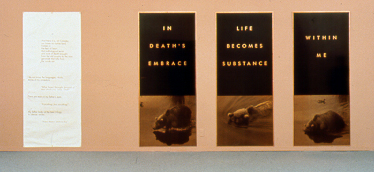

You have such a good document of photographs since the 1970s, it really is an archive in itself, they are very powerful. I was searching through a lot of your works and I came across Death Is a Natural Thing, Sweetheart and Acceptance which you produced in 1992. I was looking at your work through the visual lens of my computer, and even though I wasn’t experiencing your work in person, it still had such a profound impact on me it brought me to tears. I thought to myself, it’s unbelievable all the different ways that technology is changing our abilities to view and experience art. For you being a photographer, with the rise of social-media and the internet, how has that affected your career? Do you use these platforms?

Well thank-you! And, yes, well I’m on Facebook. I do listen very, very carefully to what people are saying and there are some very specific threads of conversations with artists across the country that we’re engaged in. For example, one of them is with Elwood Jimmy, on fear as a projection. I think it’s really helpful to be in dialogue with others when you are trying to understand these things.

I’m coming to the end of my questions, and this question is pretty open-ended for you. I know you’ve been a part of many collaborative and solo exhibitions since the early 1970s, do you have one which is the most significant or memorable?

I think the show at the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, the one we did called How Far Back is Home… which was done in 1995-96 and travelled for a long time, it also came to Vancouver. It was a really important and thoughtful exhibition put together, by that museum, which was its own museum and had been fought for by photographers across the country. We’ve lost it since, it’s now been folded into the National Gallery, but it was at a point where it had its strengths. That show travelled across the country and also went to Tucson, Arizona to the Centre of Creative Photography.

I was looking up different images from that exhibition online, do you take most of your images in black and white and/or colour?

I work with colour and black and white, now I’m working pretty much extensively with color. I’m also working digitally now.

Is there anything that makes you decide whether to do something in black and white vs.color, or digitally?

When I began I was working in black and white with archival processes and very beautiful silver gelatin prints. But as I moved along I started working with other processes like cibachrome, which was another archival process, very intense beautiful colour. Now it’s digital. I’m also working with video. I do 3D video portraits with trees, again they are performative. Looking at reciprocity, looking at reconciliation or conciliation with the forest, with the plants, with the wider than human world and still including storytelling. The wider than human world has always been the basis of the work. The land has always been the basis for the work.

When you were taking the photos for How far back is home… where you aware that 25 years later they would make up an exhibition? Was that a hope you had?

No, no, you just don’t. You’re caught in an enquiry, it pulls you along, you know what I’m saying, the inquiry has its own volition. You’re pulled into the world in a very, very specific way because of the questions that, whether you’re conscious or not, you’re trying to find direction from.

You’ve given me so much to think about, you are so well spoken, and I really appreciate you taking the time to answer some of these questions for me!

– Maddison Miller