The world premiere of the documentary Frida Kahlo at VIFF unsurprisingly adds little to the gargantuan body of work on Frida. In fact, the parts that were left out of the documentary become the most revealing elements in a film which otherwise simply mimics the tired idolizations that have propelled the last eleven films about Frida Kahlo (which, notably have been mostly from North American and European women directors). It becomes clear then that the way that Frida Kahlo is treated in cinema mirrors the way that she has been treated by pop culture: an icon, a commodity, a costume. Instead of engaging with this critically or humorously, the director Ali Ray seems to be content with recycling this Frida simulacra. Why? Dollar sign dollar sign dollar sign is my guess. And in the opening credits, we did get to see where the production money comes from: Banco de México and the Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust—which of course makes perfect economical sense. Anyway, let’s get to work discussing how this film could have been interesting, but sadly refused.

“A Woman Ahead of her Time”

As I watched this film, I felt pretty baffled trying to distinguish the layers of the global phenom that has become Frida Kahlo. But before I get into the details of the many issues with the film, let me be clear: I love Frida Kahlo as much as anyone else. Frida was dedicated to understanding her identity through self-inquiry and painting, exploring themes of queerness, disability, and femininity in a post-revolution Mexico—what’s not to love? Identity and locating politics on the body are themes that mark much of contemporary art in 2020, and Frida was doing this in the 1930s! The narrators in Frida Kahlo are right when they say “she was a woman ahead of her time.” However, the irony of this phrase is that in being ahead of her time, she seems to have caused the West’s perception of Mexican art as being stuck in time. Boxed in by an external gaze that doesn’t do justice to a nation full of vibrancy and artistic innovation.

While concepts like “Fridolatry” and “Fridamania” have extensive discussion from academics and art historians both in Mexico and worldwide (Valeria Luiselli and Tess Thackara for example), I think there is no forgivable excuse for director Ali Ray to not address them. Unless her goal is otherwise: to live inside an exotic fantasy. That is not art. That is idolization, a trap which Hayden Herrera also seems to fall into, despite being Frida’s “Official Biographer.” I put that title in quotations, because I’m not sure who gets to decide that, and in the film it seemed like the various gallerists of Mexico City had a more nuanced grasp on Frida’s art and life.

Hearing from Frida’s relatives and the museum directors of the Casa Azul, Frida Kahlo Museum, and Museo Dolores Olmeda, were welcome respites from the posh British voice of Anna Chancellor narrating off-screen in the old school style of documentary. This style, where the narrator is omniscient (and white), is meant to convey distance and objectivity. Instead, Chancellor’s function in the film seems to be to explain Mexico enough for the target audience to “discover the real Frida Kahlo,” as the film title boasts. That and to unapologetically butcher the names of Mexico City neighbourhoods (which at least gives some comic relief, if we’re being real). It’s one of those artistic choices that are so bizarre that you just really wish you could have been a fly on the wall to understand the steps to making that decision. Then, the B-roll that often accompanies these narrative parts of the film feel like a tourist highlight memory, featuring random images of fruit stands, the trajineras of Xochimilco, and dancers in the Zócalo. Me-hee-co!

The standout character in the film was undeniably the contemporary Mexican retablo artist Alfredo Da Vilchis, who said some beautiful things about Frida’s “free spirit” and the themes of the “human condition” in her work that clearly have impacted his practice. Da Vilchis’ work promotes the democratization of craft present in Mexican folk-art. He also critiques the world of “high art” and artists “who have a name.” Again, what a missed opportunity for some self-awareness in this film! It strikes me that some of his opinions must have been edited out to fit the documentary. Nonetheless, these were precious moments in the film when it felt like the gaze was Mexican.

Okay but, why did Ali Ray make this Documentary?

This obsession with Frida Kahlo is an exoticism of Mexico, and of course says more about the viewer than the viewed. What is it exactly that Europe and North America love about her?

I think that the appetite is for the struggle of the feminist artist with a Mexican aesthetic, not the Mexican artist herself, because Mexicanness is something they fundamentally can’t understand. If they did, the many other fantastic Mexican women painters of the early 20th century would share Frida’s spotlight, painters like Leonora Carrington, María Izquierdo, or Remedios Varo. Well, your loss, gringas.

Fortunately, we don’t even have to watch the film to understand the root of the fascination. We can save ourselves some time and just read the film description, which uses phrases like “feast of vibrancy” and “suffering and pain, passion,” and “radical politics, unique style.” Each of these descriptors carries so much weight.

There is particular disregard for history in romanticizing Frida’s “radical politics.” When communism isn’t convenient, we drop bombs on it, but when it’s fashion, we squeeze the story for every last dollar. What goes completely unmentioned in this documentary is a long history of Marxism across Latin America. Frida was not a lonely brilliant politico, she was part of a huge continental school of thought. Even a half-sentence explaining this would give some much-needed context. I honestly think that the ghost of Frida Kahlo is flipping the finger at this director for cutesy-ing up her politics into an exotic pulp.

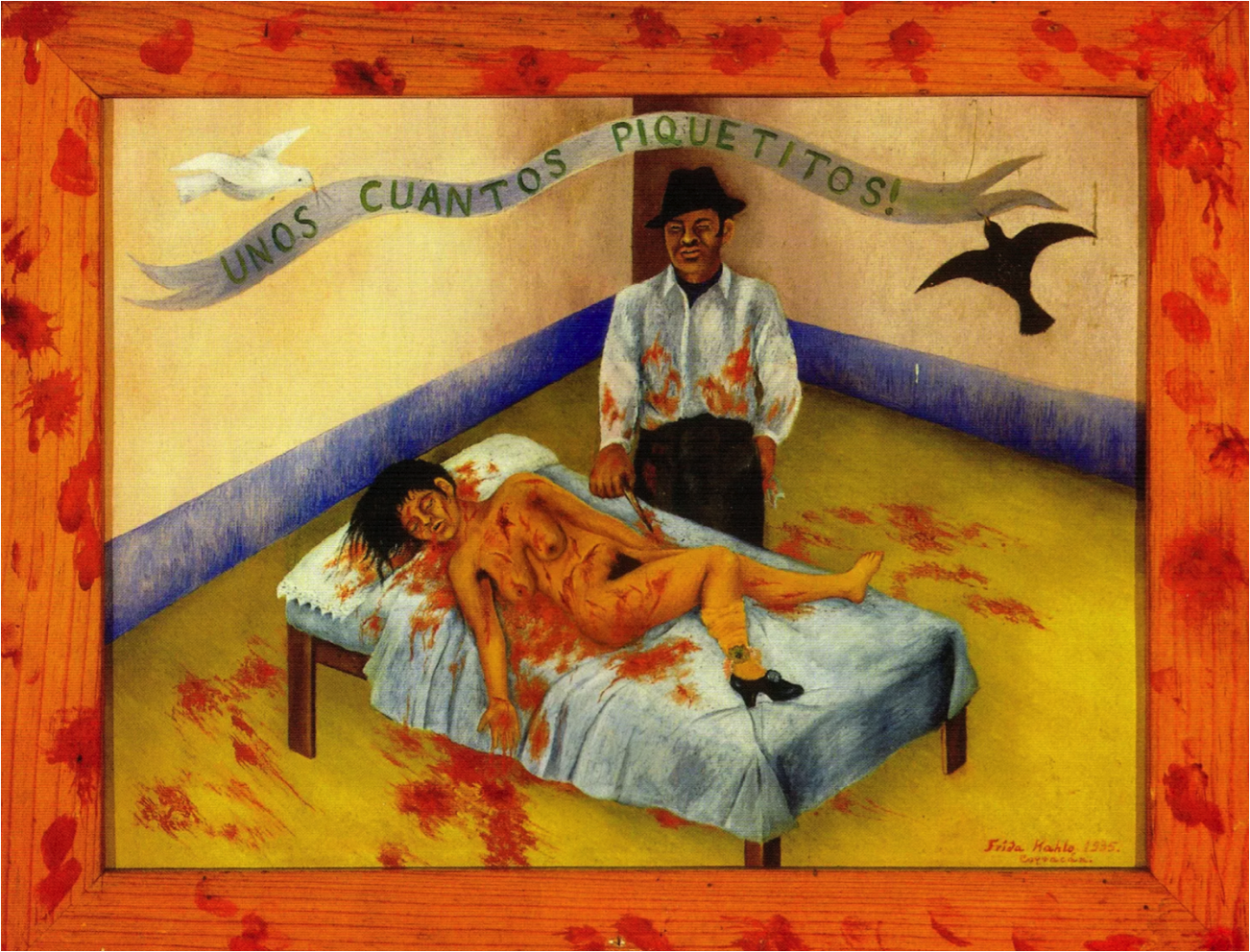

Additionally, violence against women in Mexico was a topic of a number of Frida Kahlo’s paintings, such as Unos Cuantos Piquetitos (1935), a work that deals with the femicide, which was and continues to be a huge social issue in Mexico. It is a problem that the subject of this work was not examined nearly as much as Frida’s “passion” and “strength.” Ultimately, treating Frida as this hyper-individual icon unstuck in time detracts from the issues reflected in her art. Needless to say, this cuts short the potential for social change. On that note, there is a kind of tragic late-capitalist poetry that this documentary screened at VIFF during the same weekend as a massive feminist protest in Mexico City. This documentary just can’t connect the dots.

“Unique Style”

In the film, there are many references to Frida Kahlo’s “unique style,” which is a euphemism for cultural appropriation. Frida Kahlo’s style is from Indigenous Tehuana women, which they do mention numerous times in the film with a starry-eyed envy (and also hilariously pronouncing it like Tijuana), without consulting anyone who may have an opinion on this in Mexico. This element also eerily mirrors an important element of Fridamania: the Frida costume. Which is to say, white women dressing up like a Mexican woman dressing up like an Indigenous woman for Halloween. What a mind fuck!

Now, I don’t want to get caught up in the semantics here: I agree that in a mestizo nation, our understanding and approach to Indigeneity is distinct in some ways from North America. However, the effect in this example is the same: a mestiza white woman wears Indigenous clothes and benefits for her “unique style,” while the indigenous women she’s dressing up as not only aren’t recognized, but continue to face femicide, issues of access, and constant threats to their way of life. The comparison is undeniable. Mexico is not a post-racial paradise just because of mestizaje—that same narrative excludes present-day Indigenous and afro-Mexicans (for more on this, read @migrantscribble, Manuel Abreu, Priscila Jacquier, Lutze Segu, among others). There is so much important material that this documentary refuses to even begin to scratch the surface of.

In the film, the uncritical phrase “giving a voice to the repressed” hits different because of this. A slimy feeling. To be clear, I don’t think that her being light skinned or upperclass changes the impact of what she achieved—it simply needs to be taken into account if you’re engaged in contemporary storytelling. It’s as simple as that! What’s going on! Why was there no one present who thought of this for a second in the entire production of this film!

Frida’s diaries then reveal that it was Diego’s insistence for her to dress up in what she calls “crazy Mexican dresses.” This relationship of dress and identity is reflected in the famous revenge painting Las Dos Fridas (1939). In this work, she explored her identity as being European and Indigenous, and how those identities were related to her tumultuous relationship to Diego Rivera. I love this painting and what it means for mestizo Mexican identity. Again, it was a missed opportunity to have an expert explain the nuance of these themes within the national context. Unfortunately, presenting things out of context seems to be the signature move throughout this documentary.

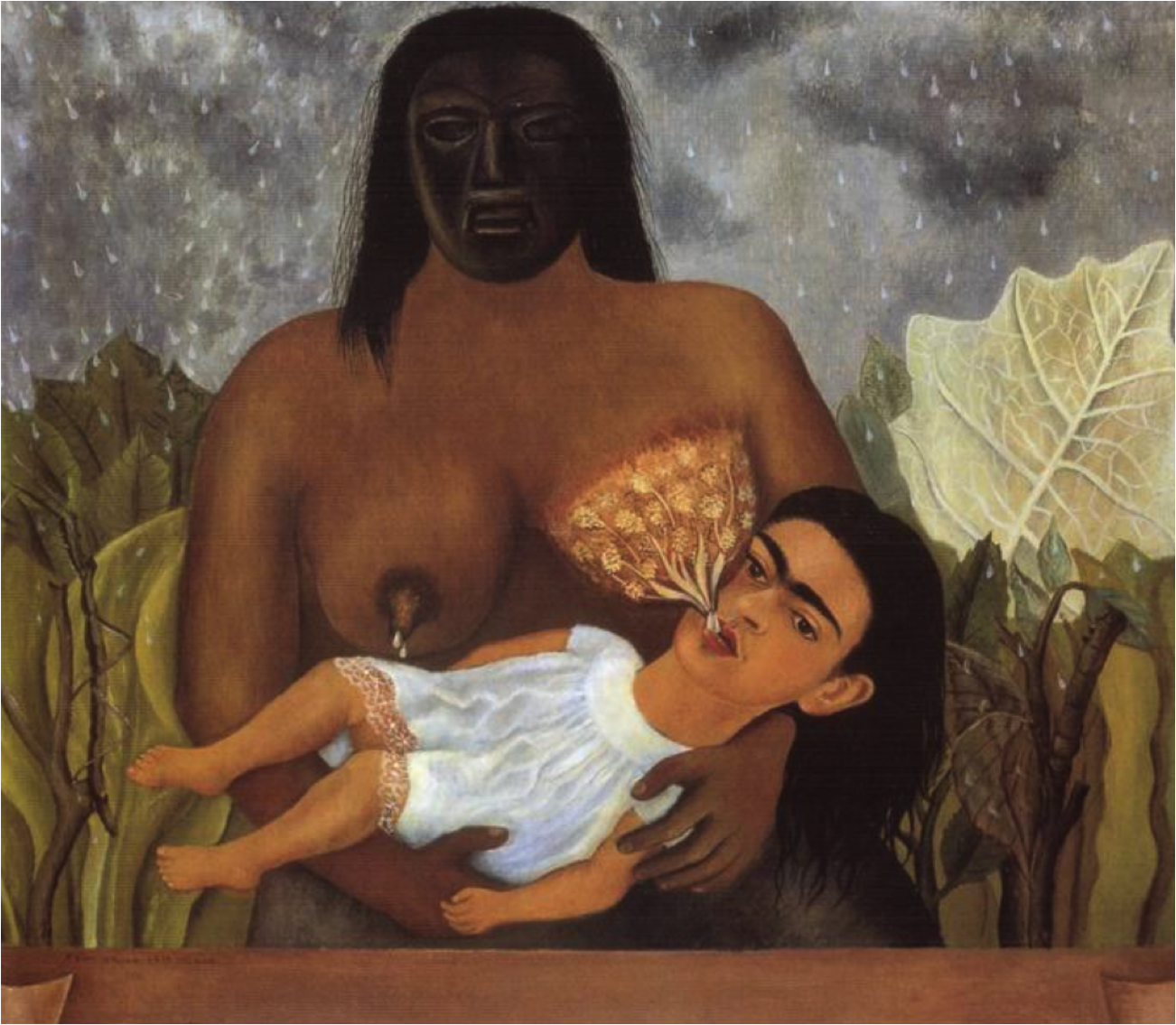

The theme of race and Indigeneity reached new peaks of discomfort when her work Mi Nana y Yo (1937) is discussed. The piece features a baby-sized Frida at the teat of a maternal Indigenous woman wearing an Olmec mask—the mother culture of Mesoamerica. She painted this piece when Diego Rivera cheated on her with her sister Cristína, who had incidentally also taken her place at their mother’s teat as a baby, relegating baby Frida to be nursed by an Indigenous wet nurse. The implications here are numerous! But of course, the academics move through this painting quickly and don’t engage with the thematic. Unable to hold complex truths and recognize the many ways this work has been interpreted, we instead get the same tepid explanations present in the rest of the film.

Behold, The Single Moment of Self-Reflexivity

There is one self-reflexive moment at the end of the film when academic Adriana Zavala refers to “Fridamania,” a phenomena that she indirectly calls “problematic.” Sadly, she does not explain what she means by this, making it feel more like a last-minute apology for a film that clearly is premised on that exact phenomena. And so, this single moment of self-reflexivity becomes an empty gesture.

After watching this documentary, I can only hope that this will be the last film about Frida Kahlo, for all our sakes and not least for the grotesquely exploited Frida herself. Maybe in doing so, we can make room for contemporary women artists of Mexico and engage with art as a means to have transformational experiences rather than a tired Imperialist museum exhibit. Besitos y bye!

Arriba el feminismo que va a vencer que va a vencer

Abajo el patriarcado que va a caer que va a caer

– Dora Prieto

Twitter: @dorajprieto

Instagram: @primadora_