When I get on the phone with Gwen Benaway for our Saturday morning, coast to coast call, it’s a happy occasion. Gwen has just become the first trans woman to be nominated for a Governor General Literary Award for Poetry. I ring in prepared. I’ve got Holy Wild, read and ready. Its yellows and pinks and blues and blacks sitting on my windowsill amongst a tangle of newly acquired houseplants. Gwen and I go on to have a chat that moves me and makes me laugh and think and learn. Afterwards, I go back to the drawing board, charged to transcribe our conversation, especially the punchy bits, and because it’s Gwen, there are many punchy bits. But in that short amount of time, the scene has somehow already shifted.

I’m on Twitter watching the unfolding of a horrifying ordeal involving the Toronto Public Library and their lending space to a feminist speaker who is consistently transphobic in her public discourse. I see heartbreaking accounts of the disrespect Gwen and her fellow protesters are being shown by TPL and their leadership. The protesters are having to explain why providing a platform to transphobic rhetoric could mean the difference between life and death for trans folk. The joy surrounding our phone call feels like from another lifetime. This invasion of joy by fear and sadness seems cruel and uninvited, but is representative of the dichotomous experience of marginalised folks, especially of trans women, and of trans women of colour.

Holy Wild is Gwen’s third book of poetry and she is currently working on a fourth. Gwen is also working on her PhD at the University of Toronto. “I would say that poetry isn’t my preferred form of writing,” she confesses, “my preferred form of writing is creative non-fiction. I really enjoy the essay and memoir writing. There’s something about the form of creative non-fiction that I find a lot of freedom and joy in.” Gwen’s essay about her choice to have SRS surgery was my very first introduction to her work.

“Poetry was the first medium I wrote in but I never felt like a good poet. I still don’t!” says Gwen, “I read other people’s work and go, ‘wow this is so beautiful, technically masterful, and skilful, and I don’t write like this at all!’ But I do feel like a proper creative, non-fiction writer. I feel capable of that. With poetry, I never feel like I know what I’m doing.” This humility is evident in Gwen’s poetic style, which displays a propensity to do the most with the least amount of words, and a natural inclination towards using everyday words to create extraordinary and sensually heightened stories and images.

The Seeds of a Writing Life

The first from her family to attend University, let alone Graduate school, Gwen’s journey into academia came as a surprise to her. “I kind of did it because I felt stupid!” she jokes, “I’m 32 years old and I applied to this PhD program when I was 30. Just like how I never felt like a proper poet, I also never felt like a proper thinker. I didn’t know if I was capable enough.” Gwen’s research focuses on Indigenous trans women and artistic production that includes writing, performance art, and visual arts. As an Indigenous Trans woman creating her own art, there is a happy overlap between Gwen’s work and her real life. There is a facility in terms of motivation and in not having to choose between real life and art. But academia, Gwen duly has found, is not without its pretences. “Grad school is kinda ridiculous! It’s a lot like high school except all the mean girls are mean nerds,” she says, “they’re still mean girls but everyone is talking in academic terms. Sometimes I find writing like that too. It’s mean girls except everyone is like, ‘the poetic register’. It’s high school. Clique-y, drama-ey.”

“Whether you’re working on poetry or essays or academic work or a job- because for a long time I worked a nine to five office job, it all takes the same intellectual labour. The labour takes different forms but it uses the same processes, you’re just adapting it to different formats.” Gwen admits she enjoys the challenge of this adaptation. “I enjoy the challenge of thinking differently, thinking broadly, and using different mediums and techniques. I love that interplay. The social part of all of these things is what I don’t necessarily enjoy.”

Gwen describes her writing life as an accident especially since growing up she had very little exposure to literature. “I wrote something and I kept going and I kept going. And suddenly here I am!” She grew up in a poor household in which books were an unaffordable luxury. There was no TV or radio because her family was conservative. Gwen started visiting the local libraries but wasn’t allowed to check out books before having them inspected by her parents. “I’m not sure how I came to be a writer but it was probably through clandestine secret readings at the library. I used to get bullied a lot. Like really bad,” she says, “instead of going to class or being in the hallways- because I’d get attacked in the hall, I’d just hide in the corner of the library of my high school and read all day long.”

One day, completely out of character, Gwen’s father came home with a box of paperbacks for sale at the local store for $3. The paperbacks happened to be Mercedes Lackey’s fantasy fiction, which became Gwen’s gateway into the world of reading and writing. This infatuation with Mercedes Lackey’s work led her to other fantasy heavyweights: Tanya Huff, Melanie Rawn, and Robin Hobbs. “I eventually started reading other stuff like Alice Munroe, you know, the canon of writers that we’re supposed to read? But I kept reading trashy fantasy and werewolf murder mysteries”. In her twenties, Gwen became interested in a lot of contemporary Canadian poets. “Katherena Vermette’s North End Love Songs changed my life and opened up possibilities in poetry for me. Katherena tells such beautiful and profound stories in small spaces. Her very precise and masterful images influenced my writing. She has won a Governor General Award.”

And now so will Gwen.

We both sit back and reflect on that for a moment. It’s 2019 and there is finally a trans writer up for recognition in the literary sphere.

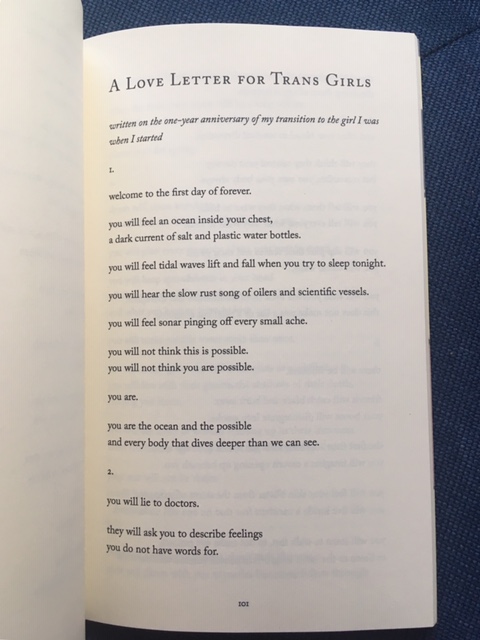

The Writing Community

Gwen acknowledges the difficulty of coming across trans narratives written by trans writers. “Trans literature, especially trans literature written by trans women, is a very small category. It is the most erased category. I didn’t find trans narratives until I was transitioning,” she says. “That’s when I discovered the works of Kai Cheng Thom, of Trish Salah – one of the first trans women in Canada to have a collection of poetry published. Trans women writers have been ignored, critically and always. Kai Cheng and Trish really helped me grow as a writer and a person. I’m so honoured to be in conversation with them now.”

I ask Gwen whether bringing the control of storytelling back to the trans community was one of the drivers for her wanting to become a writer. “Writing can do a lot for the world but it can’t fix the world. Fixing the structural problems that we’re living with? That we actually have to do with our own labour,’ she says. “Maybe writing can show us a way towards it but I don’t think people should become writers to fix something. If you write you should write because you love it. Because it’s a skill and a practice you value. A lot of people I know want to become writers because they want to change something or be famous. But at the end of the day, the only thing that will keep you writing is if you enjoy the nuts and bolts of it. The sitting down by yourself at 4 am writing of it.”

“We also have to understand that the writing industry is an industry. It turns people into products and commodities. It sells ideas. It’s very hard to change the system when you’re being brought into it,” reflects Gwen. “We always talk about the politics of representation and having more of it. That is valuable but representation by itself is not going to liberate us or change the systems of oppressions.”

Representation of minorities in Canadian writing spheres nonetheless is on the rise and the bipoc writing community in Toronto is a great example of this. “There is still a lot of racism, sexism, and transphobia in writing spaces but there are wonderful and beautiful people in the community as well. Writers like Canisia Lubrin, Whitney French, and Carrianne Leung. I have a great Indigenous writing community with writers like Billy-Ray Belcourt, Joshua Whitehead, Arielle Twist, Lindsay Nixon, and Alicia Elliott. I am part of a community of trans writers that includes Kai Cheng Thom and Casey Plett. These are all my closest friends, the people I bounce work off of, whom I share drafts with and talk to. We function as a little community, and truly support each other, which is really beautiful. That’s something that I haven’t seen other groups of writers do. “

Gwen’s writing communities in Toronto are #squadgoals but the overarching writing world, in general, is often a very exclusive and elitist place. “At a certain level, writing is very much about rich people. You realize that when you walk into a writing gala and everyone is in designer wear. These are people who make a lot more money than you and you’re there to entertain them,” says Gwen. “People who become really successful writers are often from high-class backgrounds and are independently wealthy. Or they make a lot of money writing, which is hard to do. Or they have teaching jobs or speaking gigs and they just sort of class level-up and the next time you see them they’re in Louis Vuitton. Class is a fascinating function in the writing world. It’s funny that people don’t talk about it! I find it very odd.”

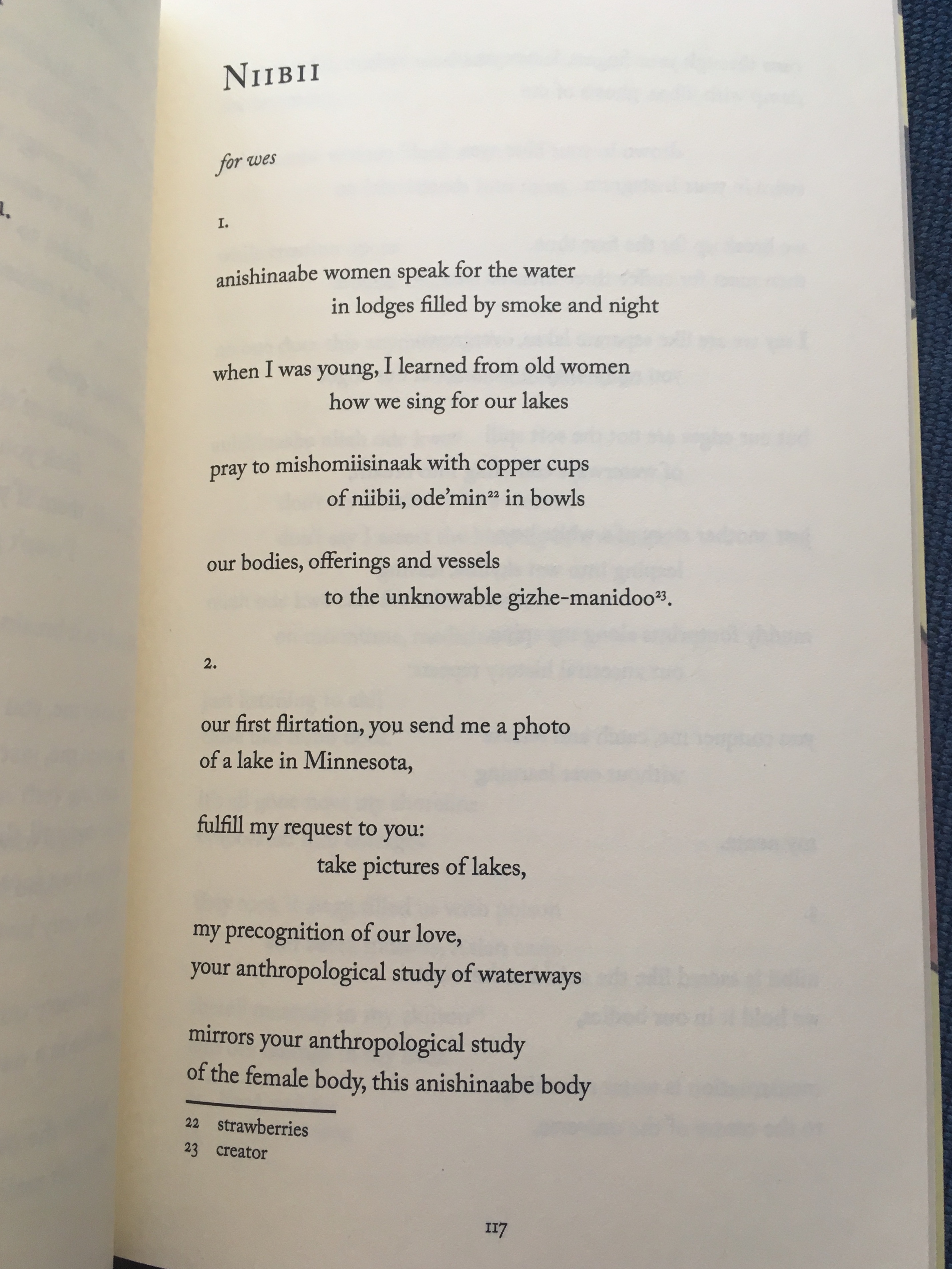

Holy Wild

Gwen wrote Holy Wild in pieces over the first year of her transition. Pieces that Canisia Lubrin, her editor, helped put together. The poems are interwoven with Anishenaabewomin lines that form an integral part of the narrative and its voice.

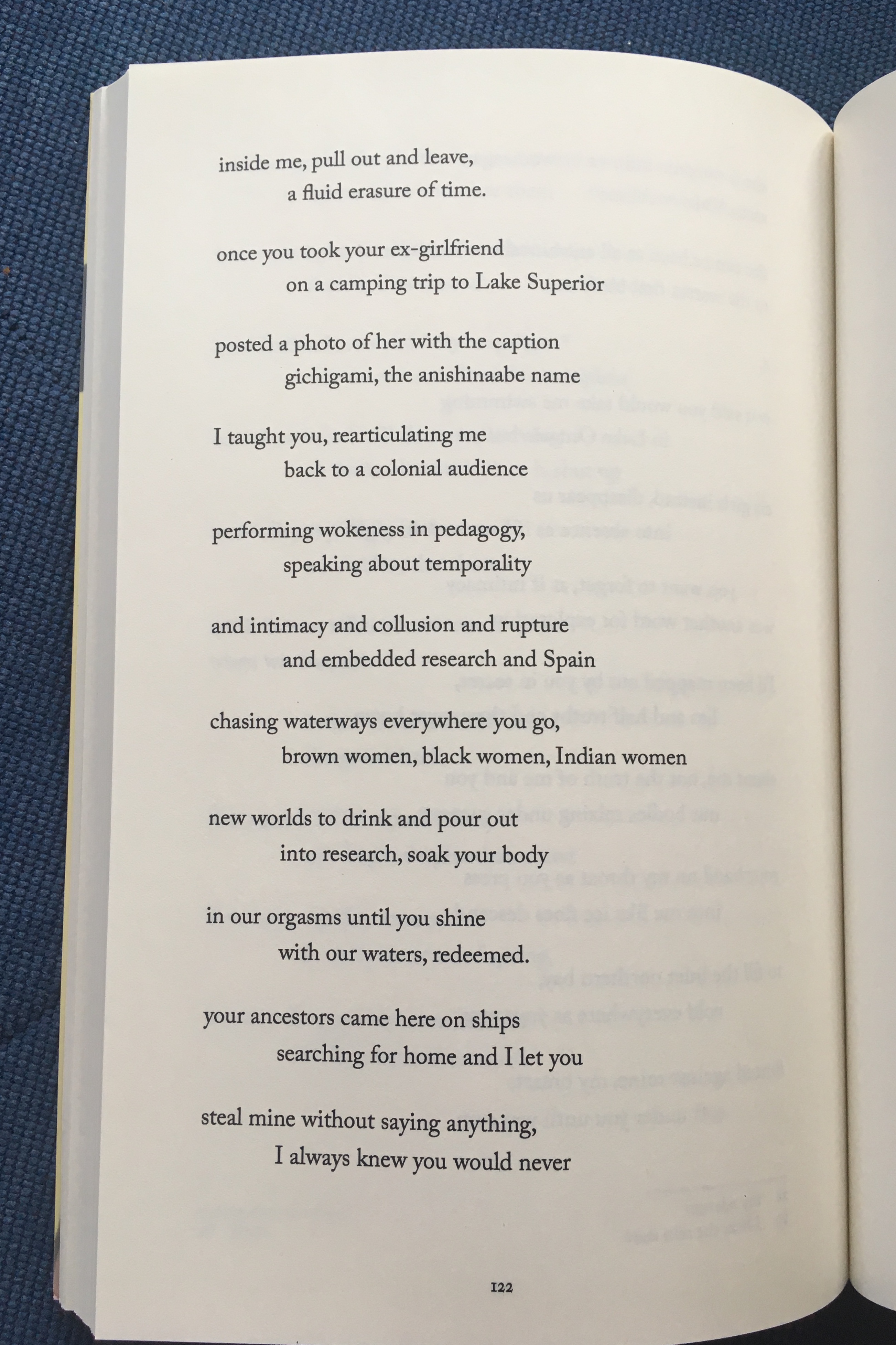

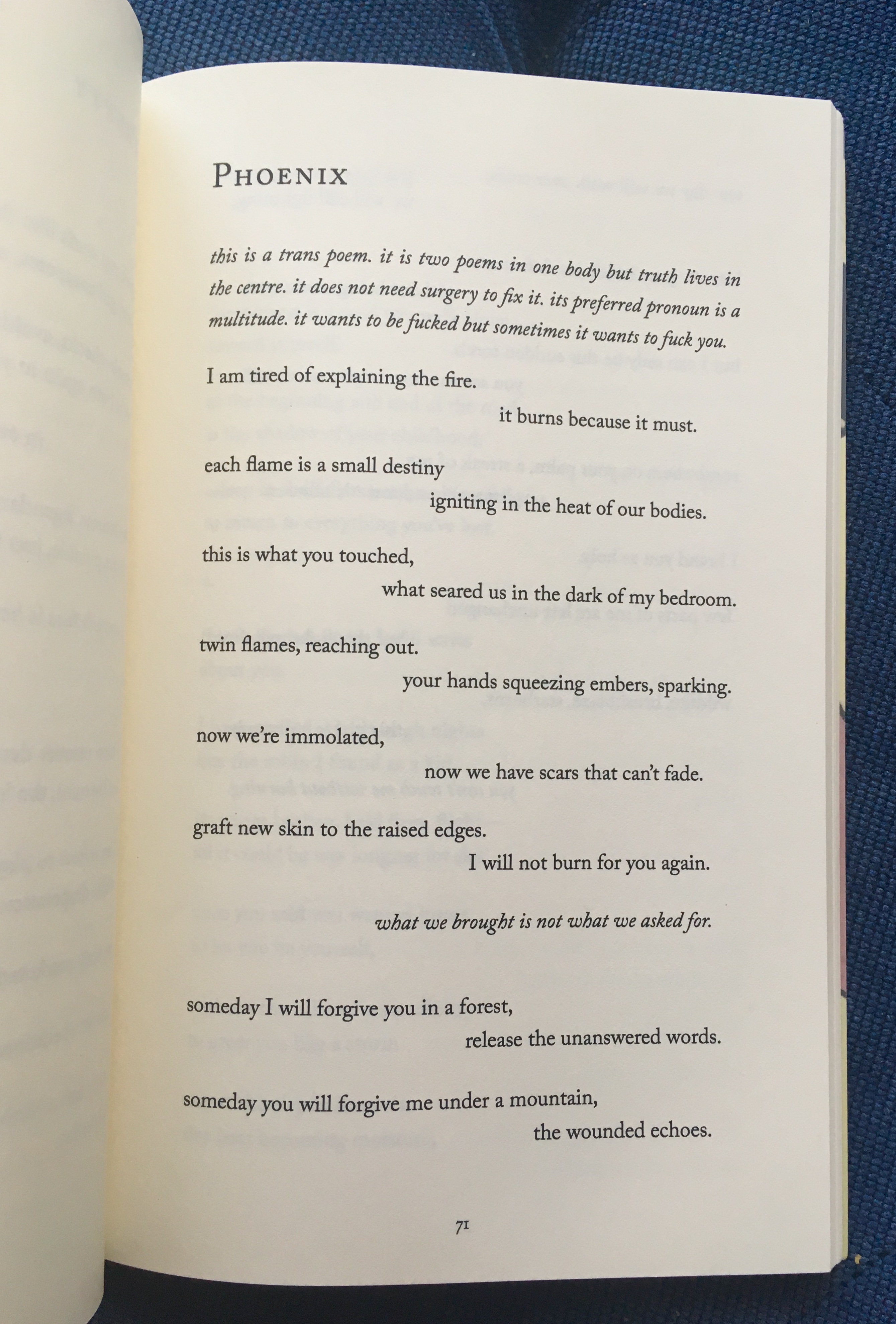

I was able to relate to Gwen’s poems in Holy Wild like I’d never related to anything else before. Her unfiltered and unabashed honesty took me to places that I’ve been as a cis-woman of colour in my previous relationships with straight white men. Relationships in which it was never said outright but always understood, that I was somehow second best, a filler, the appetizer, the thing you do to prep for the real thing. I recognized the subtleties of these interactions in Gwen’s poetry. I recognised in her lines my automatic assumption of an inferior role in relationships at first, and then a subsequent and livid rejection of it. Everything suddenly came into focus as if I’d just spotted bright red writing hidden on an elaborately graffitied wall. To see my distressed thoughts justified and the anatomy of textbook gaslighting manoeuvres laid out as clear as a Monday in spring, were both revelatory and liberating. The similarities between Gwen’s and my experiences were numerous. I had finally been given words to put to experiences that, quite frankly, had fucked me up for a long time and that my loving and patient partner had to undo. In relationships where there is an imbalance of power, due to gender, race and/or class, there is often abuse of power that is enabled, and perhaps encouraged, by a faulty societal infrastructure that is in turn, inextricably rooted in colonialism. Gwen depicts this abuse of power with elegance and objectivity, and in her words, keeps it real. I felt close to Gwen’s experiences as a trans-woman like I’d never felt closer to a cis-woman’s experiences before.

Gwen showcases the giddiness of new love and its possibilities in Holy Wild. She recreates the excitement of two very different people coming together. She shows us how the collision of their differences creates an explosive, super cloud of beauty. But this beauty doesn’t last long when the real world and its social structures come a’ knocking, because power is meant to be kept within certain circles and it isn’t meant to be leaked. Non-marginalised folks know this. They got the memo. The marginalised parties who brush against this power learn through heartbreak and disappointment about the silent dedication of the non-marginalised to uphold these power structures.

The closeness I felt to Gwen’s experiences also came with a sobering education. Always accustomed to seeing myself as marginalised, I came face to face with the privilege of being a cis-woman through Gwen’s work. I realised just how much I can, at any point, contribute to transphobia if I don’t pay attention to my words and actions. The fear I feel when I come home late at night clutching my keys in my fist, is multiplied a hundredfold for trans women. The danger, the trauma, the stress of existing, these are realities that cis-women get a taste of but never face at the intensity that trans women do. For me, Holy Wild was a combination of relating massively and then learning and understanding closely.

“My first audience is always other trans women. That’s who I write too,” says Gwen. The reception of Holy Wild has surprised her. “I have had a lot of people from different backgrounds and with different experiences reach out and say ‘this really mattered to me’ or ‘I’ve had these experiences, thank you for writing that.’ That felt really good. I dedicate this book to ‘girls like me’. And ‘girls like me’ is really open.”

Holy Wild paints a very visceral picture of modern relationships, and specifically, of the experiences trans woman have in the modern dating world. Gwen generously shares stories from her personal relationships, which I can imagine, must have been beyond scary, but seems necessary to expose the social hierarchy that straight white men create and take advantage of. “I’m here for this question!” Gwen says with excitement, “I mean, I think my ex-partners are probably really upset about what I wrote. But like, ‘deal with it?’ is kind of how I approach it. Because I’m like, yeah, this happened and this is my life, I’m sorry that you sound like a transphobic asshole who did a bunch of really violent horrible things but also, that’s what happened so deal with it!” For the most part, Gwen is now comfortable with this new exposure but what still stings like the first time is the violence that continues to imminently exist in every one of her relationships with straight men.

“The ways in which trans women in intimate relationships are violently oppressed don’t get talked about. People have a reluctance to acknowledge that trans women face this violence constantly. Violence is an integral part of our lives and so I always try to write towards it,” explains Gwen. “There are all kinds of oppressions that I encounter on the daily but encountering transmisogyny through my intimate partners is the most painful because these are the people that I love and trust.” While straight white men bear most of the brunt of inflicting this oppression, the rest of us – especially cis-gendered folk, are complicit in upholding it. Cis-women, and cis-white women in particular, benefit to a great degree from the assignation and divisions of gender, which ultimately dictate how trans women, especially trans women of colour and trans Indigenous women, are treated, romantically and sexually.

In Gwen’s stories, walking side by side and hand and hand with this violence, are joy, beauty, the madness and novelty of new love, and the spiked fury of sex. Her poems recreate modern-day romances staged against the high definition pixels of technology and social media. “Kai Cheng Thom has said that for trans women every experience in life is often about violence and punishment. That’s how transmisogyny works. And so yes, when you say that there are love and beauty in these relationships, there is always violence underneath that sooner or later finds you. You have to hold that violence at once with joy and pleasure.”

Self Love, Self Care, and Moving Forward

“When you’ve gone through the same process of transmisogyny in relationships, ten or twelve times with different people, you get used to the script. You confront the same form of transphobia over and over and over again. It’s constant re-traumatisation. You realize it’s not you, it’s not even the other individual per se, it’s this whole collective violence.”

I tell Gwen about the time I saw her read her poetry at the University of Toronto before Joshua Whitehead went up on stage. She had the audience in stitches. She was a sunny picture of sass and laughter. It’s hard to fathom that her body then was carrying the weight of years of trauma at the same time. “I mean. Anti-anxiety and depression meds!” she laughs, “having a dog really helps me too. My dog Bravo is good support. Honestly, I don’t do well. I’m not always having a joyful life. I struggle quite a bit and I have trauma. The way I live my life has changed because of violence and I have to accept that. For a lot of trans women that I know, there is joy and positivity, and there’s all this pressure on us to be positive role models, but a lot of us are struggling because it’s really hard.”

Gwen’s next book of poetry and her next book of essays both continue in the same vein of exploring the complicated nature of romance for trans women. “Trans Girl in Love is a more detailed explanation of my experiences of romance and love. My fourth book of poetry, Daybreak, is also about love and intimacy but it’s also about my life after surgery. It’s about trying to heal in the wake of sexual violence. It’s a lot of lesbian poetry too, as it’s about my first romantic and sexual relationship with another woman! Daybreak is really about the possibilities and limitations of being a trans woman in the world. I’m so excited for people to read it.”

As I conclude the interview, I ask Gwen to share her message to young trans women who are excited to see her get the Governor General nomination and will continue to look to her for strength and pride. “That’s so hard of a thing,” confesses Gwen, “I would say what was said to me: it doesn’t get easier but you do get stronger and more capable. And that I think is true. It doesn’t get easier to be what we are in the world but you grow and in your growth, there’s all this possibility for joy and freedom.”

I take a look online and see that there will now be an official protest, organized by Gwen and her friends, at the Toronto library in honour of protecting trans lives. It will happen two days before the announcement of the Governor General prizes. Gwen won’t even be able to sit tight in her living room, feet up with a glass of wine, in anticipation of this badass honour. She won’t get to revel in the sweetness of her achievement. Instead, she’ll be at the library negotiating the humanity of trans folk, as if it were a thing up for debate, which it ridiculously is.

That dichotomy of joy and pain?

There it is again.

*************************************

“Holy Wild” is available for purchase at your local bookstore. You can also follow Gwen Benaway on Instagram and Twitter.

– Prachi Kamble