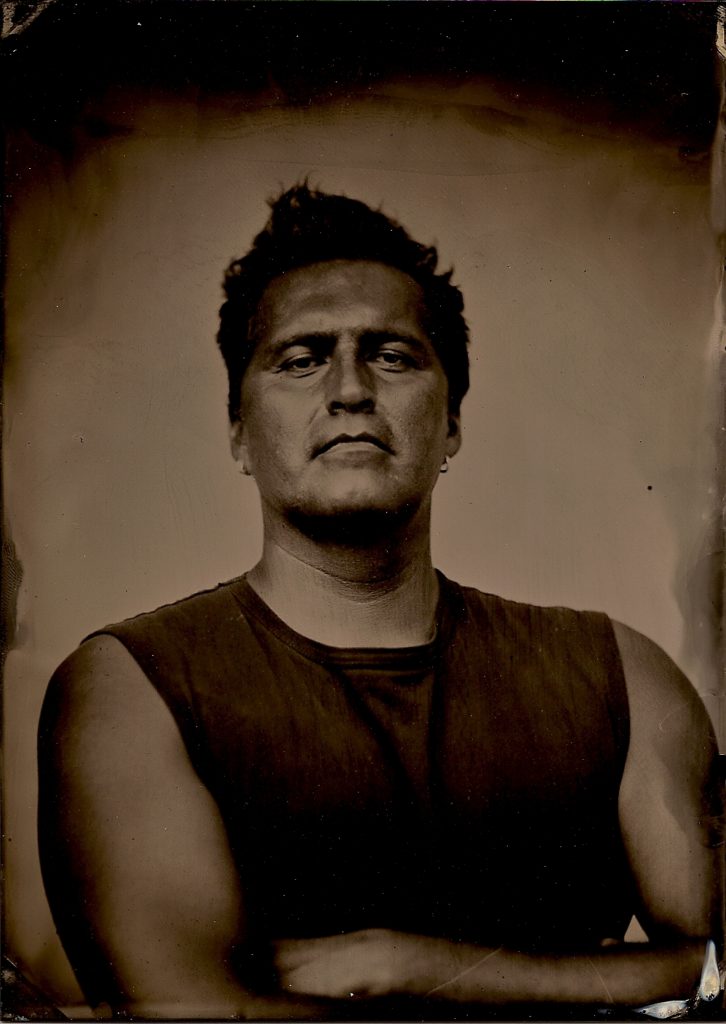

Never one to shy away from controversy, Canadian visual and performance artist, Adrian Stimson, has been asking difficult questions with his art for decades. He has done so with humour and a perspective like no other. Often drawing from his Siksika (Blackfoot) heritage, Stimson’s work challenges our ideas about social justice, sexuality, Canadian identity and indigenous culture. Having garnered praise for his exhibits around the world, this year, Stimson’s hard-hitting contributions to the world of Canadian art, have received recognition from the Canada Council for the Arts in the form of the prestigious Governor General Visual and Media Arts Award.

Stimson’s installations speak to the residential school experience, genocide, loss and resilience. He has curated photography, and constructed performance dioramas and war depictions. One of his sculptures was in collaboration with relatives of Murdered and Missing Women. Stimson’s installations have featured life science replicas of bison, an emblem of indigenous culture, and characters such as that of Buffalo Bill, which subverts the stereotypes of First Nations peoples.

Stimson also participated in the Canadian Forces Artist Program, which sent him to Afghanistan and has been awarded the Blackfoot Visual Arts Award in 2009, the Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal in 2003, the Alberta Centennial Medal in 2005 and the REVEAL Indigenous Arts Award – Hnatyshyn Foundation.

I called the prolific artist to chat about his motivations behind the provocative art and his personal journey through the choppy waters of self-discovery and artistry. Given the gravity of Stimson’s subject matter, I did not expect the voice at the end of the line to be emanating with sunshine and ringing with warm laughter. But it very much did and below is the conversation that left me inspired, ignited and enlightened, all at once.

How does it feel to be recognised and honoured by the Canada Council for the Arts, as well as the British Museum, especially since your work challenges the actions of the government in the past?

Well, it’s interesting you know. I have two minds about it. First of all, with the Governor General Award, the Jury comprises of a group of my peers so I deeply respect the process. It’s very honouring. I truly appreciate it and I’m very excited about the recognition. At the same time there is some internal conflict, given my colonial projects and being part of the colonial system. When these moments come along you have to look at them from a different perspective. I think of the younger people, especially those who are setting out in careers in the arts and especially in my Nation, whom this recognition might inspire. It will show them that regardless of the challenges we face as indigenous people in the system, we do have opportunities.

What art were you exposed to growing up in the Siksika Nation and when did you realise you wanted to make art for the rest of your life?

I think I always wanted to be an artist. As a child, I gravitated towards drawing and painting. I got sidetracked into many other careers but I always took time to visit art galleries. There are also many artists in my family here in the Nation.

I grew up across Canada, in Alberta, Ontario, Northern Quebec, James Bay, and Saskatchewan so I’ve been exposed to many art practices, from the Inuit to Cree to Anishanabe. That really influenced me. Storytelling is a natural part of my identity as a Blackfoot person so there were no second thoughts that this was what I was going to do.

Can you tell us more about the characters you frequently use in your performance pieces like Buffalo Boy and the Shaman Exterminator? What about these personas make them keep surfacing in your work?

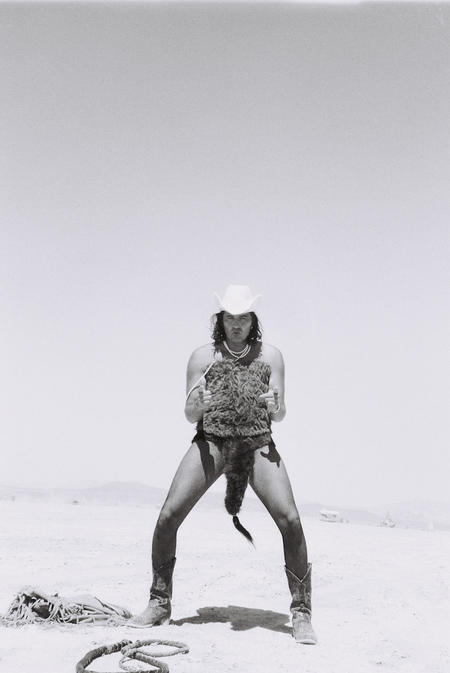

Buffalo Boy comes from my research on Buffalo Bill and his Wild West shows, the narrative of those shows and how those shows played a part in identity building of indigenous people, specifically plains tribal people. Given the ideas of humour and parody in it, it was a natural choice for me. Developing Buffalo Boy involved looking at my own history as a two-spirited person, queer history and Blackfoot history, and my grandfather being an Indian Cowboy in the Calgary Stampede. I funnelled ideas of social justice and the history of colonialism into Buffalo Boy.

Buffalo Boy’s alter ego is the Shaman Exterminator, who is basically Buffalo Boy under a bison robe and a big, long bison horn. He is an ominous character. He stemmed from the idea of semi-villains who have good hearts. Through him, I get to look at the history of shamanism and how this image is normalised and appropriated in western culture without basis in indigenous history. The Shaman Exterminator is a bossy, big bull in a china shop. Lord of the Plains is an extension of the Shaman Exterminator. He’s a pompous clown character. He has big white hair, white powder puff face, and likes to eat cupcakes with tea! He’s a portrayal of the colonialist settler person. Those three characters go together at different times depending on the situation.

What about “150 Blows” which you presented most recently?

“150 Blows” was made in response to Canada’s 150th birthday in Toronto, Saskatoon and Montreal. For it I embodied a creepy porn doctor with a porn moustache and got 150 people to pose for me. They came into a doctor’s office that I had created with an examination table and desk and lighting. In the background you could hear 70s porn music. Then I appropriated a government webpage where they talk about Canada’s 150th birthday and totally sexualised it.

The idea was to present how conflict and conquest are often described as raping and pillaging. Often with conquest comes sexual victimisation, especially of women. So I asked people to come in and before I took their portrait I asked them to remember the best orgasm they ever had and make that face. Everyone who participated made all these crazy faces and it really sort of looked like “ooooooooh! Canada!” It worked on so many different levels. Then I painted my body white like the classical European bust and stood between two panels of the ends of the Canadian flag and had the orgasmic faces projected on my face.

You have also performed at Burning Man. Can you tell us about those performances? What attracts you to the festival?

I’ve gone to Burning Man 13 times in my life. I’ve taken Buffalo Boy there several times, whether it was for photo shoots out in the desert or performing or walking around the city. The Shaman Exterminator did a crawl as well. The theme that year was the Green Man, and it was all about environmentalism. There was a definite lack of indigenous participation and indigenous presence, given that indigenous people are often looked at as the original environmentalists.

Do you feel that the foundations of Burning Man are borrowed from First Nations values?

There are many aspects of Burning Man that are borrowed and appropriated from indigenous knowledge systems. But it’s also a pretty unique amalgamation of different ideas and philosophies. It’s anarchist in a way but also not. It’s also grown so much. When I first went, there were 19,000 people and now there are 70,000. With that have come its own problems, like appropriation. Generally speaking, if you go to Burning Man you’ll find what you’re looking for. And you’ll have a lot of fun. There is so much amazing art and so many amazing performances, and so much that I have benefitted from.

You are known to weave whimsy and humour into your work. Do you find it important to approach your work with optimism even when you’re dealing with heavy subject matter?

Oh absolutely, humour is so important when looking at history. There are some pretty horrific, heavy histories out there, especially for indigenous peoples. For us humour is a survival mechanism. We’ve always had to look beyond hurt to a place if comedy and humour. In my practice, I like to say, that I tickle people and then slap them.

Humour opens people up so they don’t feel intimidated. It’s the best way to start understanding history.

With the rise of social media and technology do you find that it has become easier to make people more open-minded, bring awareness to the crimes of our colonial past and also to empower First Nations youth? Easier since we talk more about oppression, misogyny, homophobia?

Social media is a tricky space. I see how it’s opened up a world of information but as we know from recent developments it’s highly manipulative. I think we have to be cautious with it even as it furthers knowledge and allows people opportunities.

We need to be diligent in how we use these platforms. Having said that it has allowed me to put out my work and reach more people. There have been times where once I’ve had discussions with people on social media they go “oh I get what you’re doing!”

What about the role of social media in connecting indigenous youth to each other?

Here on the Nation we have something we call the “moccasin telegraph”. You tell one person and by the end of the day the entire nation knows what is going on. It’s also been interesting to see the diversity of indigenous perspectives. People assume that all indigenous people think alike. We don’t! We all come from different tribal systems. I’ve seen some great debates around issues of identity and appropriation. Social media has been great for connecting with each other in solidarity and also in opposition, when need be.

You make art in different formats: you paint, you sculpt, you perform, and you create installations. How do you move between your mediums? How do you decide which you want to dress your idea in?

It has to do with intuition. I did my Undergraduate degree in painting so my first love is painting. I see the rest of my work through the eyes of a painter. One day during my Undergraduate I was sitting on a hill and looking at a tree, and examining it and dissecting it- almost to the follicles of the tree and really seeing it. It really struck me how artists look at the world differently from the general public. We really take time to pull things apart and put things together. Depending on the subject matter or situation I come to a determination right away. It depends on the research too.

You’ve been making art since 2010. Was it an organic and smooth journey? Were there challenges especially since your art was bold and unconventional and so in those instances how did you not succumb to pressures to make your art palatable? Were there years when you were blocked?

Every artist will tell you that it is a struggle. We’re basically entrepreneurs. We’re our own administration, promotion, sales and communications. It takes a lot of work. I feel a lot for young artists today. I still have to ask, “Ok where is the next gig coming from?” I’m very lucky now that I can ask a bit more for my work but for the longest time my work could only sell for so much. It takes time and determination to be an artist.

You have to do things that make you happy. What is it that turns you on? For me, art has always been that. Because of this, during times of struggle I was able to look ahead and keep going. In the end something always comes up.

I’ve been really lucky as an artist too. I was able to work in art galleries, I was a program guide helping artists create their work, then I was an artist in residence, then a curator in residence, then an assistant curator, and now an independent curator.

The goal was to create an environment for myself every day where I could be inspired. The key is to have the energy and to always keep moving forward. It’s not easy but if you’re determined I personally believe you can do anything that you want.

What is your creative process like? How do you stay inspired?

I begin with a lot of research. There are times where I free flow. When I want to paint I just do it, but generally, I try to fill my head and mind with issues that impassion me, like social justice, environmentalism, racism etc. I fill myself with those to the point where I need to regurgitate that and spit it out as a painting or performance or installation. As an independent artist there is a lot of administration like organising shows, shipping stuff, printing things for people, sending images, finding grants and funding, providing galleries with work that sells, workshops and residencies.

I’m home now and starting to create a permanent studio. I’m looking forward to having a big space to create in and spreading out with all my stuff. Part of research is collecting things over time and using it when the time comes. I have personally never experienced any real blocks. I have my days though like after a big project I get tired.

Since 2010, how do you think your art has changed along with the Canadian consciousness? Do you feel that you’ve found answers to the questions you set out to ask in terms of identity, culture, racism, and homophobia?

I graduated from my Undergraduate degree in 2003 and did my Masters right afterwards in 2005. There has certainly been a shift in ideas since. When I first started doing Belle Sauvage & Buffalo Boy: Putting the Wild Back in the Wild West with Lori Blondeau, and we dressed people up in kitschy Indian headdresses, the issues of appropriation hadn’t even been discussed. Perhaps we opened up the door for that. I’m happy to have been part of the vanguard of that movement. Having said that, there’s still a lot that we need to understand and work through in relation to cultural protocols and practices between tribes. I’ve run into opposition too where some indigenous people think appropriation is perfectly okay- these are just objects, what are we worried about?

These are very interesting discussions, especially on issues of social justice and conciliation. People always say “reconciliation” but I don’t know what we’re re-doing when it’s never happened before! It’s conciliation.

In terms of artistic practice, discussions like these have opened up space for artists. I’m so happy to see so younger people challenging their rights and challenging the status quo and authoritarian voices. We have so much to be concerned about right now, the environment first and foremost.

Do you feel hopeful about the new Trudeau government and can we ever undo the wrongs of our past?

Politics is one thing and human beings are another. The only way conciliation will happen is if change happens on an individual level. I often ask people “Well how many indigenous friends do you have?” And a lot of people say “oh geeze none!” You know it might be good if you found some (laughs). With that will come discussion and ultimately understanding of Canada and Turtle Island.

Sometimes I’m sceptical and not very hopeful about our political process. You get an apology but the actions don’t match the words, so there are hypocrisy and disillusion that come with that. But there are lots of people doing great work and who are allies. That’s happening regardless of political processes.

Justin Trudeau like any other human being has his good sides and his faults and often the political process stymies individual desires. I’m sure he thinks a certain way about things but because his party believes something different he doesn’t always get what he wants. Everything is so manipulated in politics that it makes me wonder how anything ever gets done!

What is the relationship between indigenous cultures and queer identity?

Indigenous cultures are very supportive of the queer identity. With the colonial project came the erasure of two-spirited people in the Americas. Years ago I wrote a paper called “Too Two-Spirited For You: the Absence of Two-spirited People in Western Culture and Media”. My research looked back to Columbus, Balboa and the conquistadors who were confounded by two spirited people- men who acted like women and women who acted like men. Two-spirited people were very much integrated into the community and were a very important part of the community. The settlers got rid of them because of Western Christianity and its morality, as they were often the leaders, the spiritual people, and the medicine people.

If you research all cultures you will always find homosexuality. We’ve gone through a long period of morality and violence around morality. For me being a two-spirited person is highly respected in my community. My community also went through a time when western Christianity came in and tainted our history. But there’s been an explosion especially amongst young people of bringing back those cultures. It’s been a great experience being part of that movement and reminding people of that part of lost history.

What advice would you give First Nations artists who are looking to tell their stories and voice their opinions?

Oh just go for it! Be fearless. You’ll learn a lot. Sometimes you’ll get a hard knock and other times you’ll get great applause. If art makes you happy then do it. Find a medium that speaks to you. Explore and experiment. We do come from communities where there are high suicide rates among young people and high addiction rates. Right now in my Nation, the tribe near us has opioid problems. There are so many obstacles out there.

Art has saved me in so many ways. Even though at times the world looks bleak it’s absolutely beautiful too. As artists we have the ability to look at both and learn to tell our stories through that.

As an artist how do you find the courage to be bold and address issues that have the potential to make especially white Canadians uncomfortable? Do you think this is the purpose of art? To be evocative and provoke reactions?

I think art can inspire in many different ways. Some of my favourite moments are just looking at a beautiful painting and having it move me. I remember looking at Michelangelo’s David in Florence and being awestruck.

I see my work as a trigger. I can’t do anything to change anyone’s mind. People themselves do that. They bring their own histories and experiences to the gallery, and looking at a painting triggers something within them. So really they’re doing all the work. Hopefully, it allows them to further explore their feelings and learn about issues and histories.

When you look at the whole residential school history and genocide in the Americas, the fact is that many people don’t know very much about it. Hopefully, the work urges people to examine their histories. To look to the future we have to look at the past. Art plays a major role in that.

Are there any artists that are your favourites whom we should check out?

When I was starting out I held many First Nations artists in awe. Like Rebecca Belmore, Shelley Niro, Robert Houle, Norval Morrisseau, Alex Janvier, Joane Cardinal-Schubert- all the trailblazers. For the longest time I was a fanboy, next thing you know I’m meeting them, next thing you know they’re my friends! It’s been really surreal.

What themes do you see yourself tackling this year in your art? And will we get to see your work in Vancouver soon?

I’m itching to get some paintings done. I want to push myself in different directions this year. I still like including the buffalo and the bison in my work but I might want to subvert that a bit.

I’m going to be building a bull boat at my residency in Toronto. They were these round boats that the Blackfoot used. My work as an artist also is to revive cultural practices. I’m also doing work on bison robes of the Blackfoot people. I’m doing winter accounts and war accounts on buffalo robes through petroglyph images.

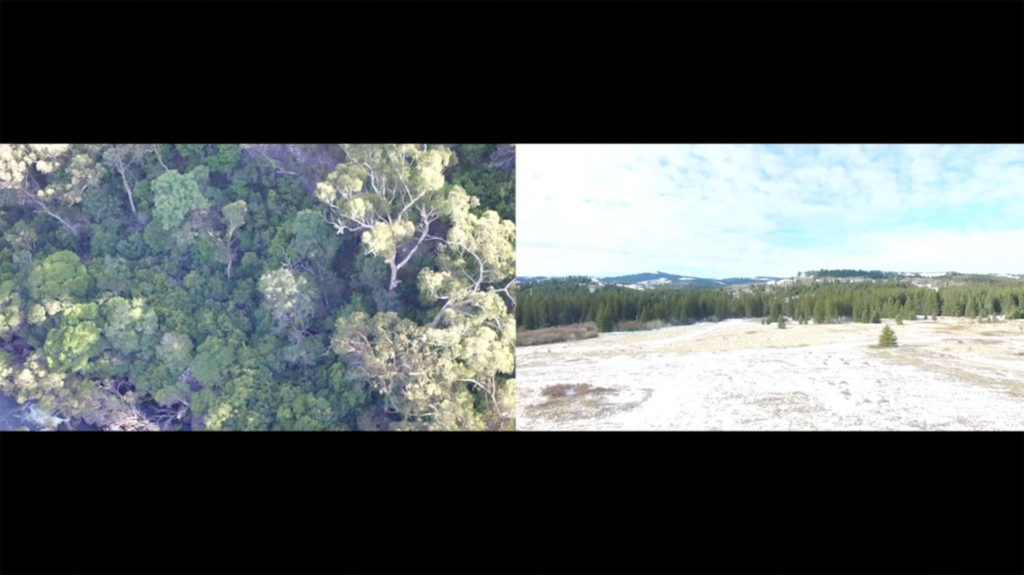

In Vancouver, I am scheduled for a performance at the Queer Arts Festival in their new space. I’m also travelling to the University in Kansas to do research on two-spirited people’s history in the Americas. I have an exhibition coming up in London and I’ve also been doing research in Australia on parallels between indigenous peoples on both continents. I’m also building a residency here at home so lots of building and planning here!

-Prachi Kamble