The Giller Prize-Winning Writer on Craft, “Reproduction”, Academia, Workshopping, and His Pandemic-Edition Creative Process

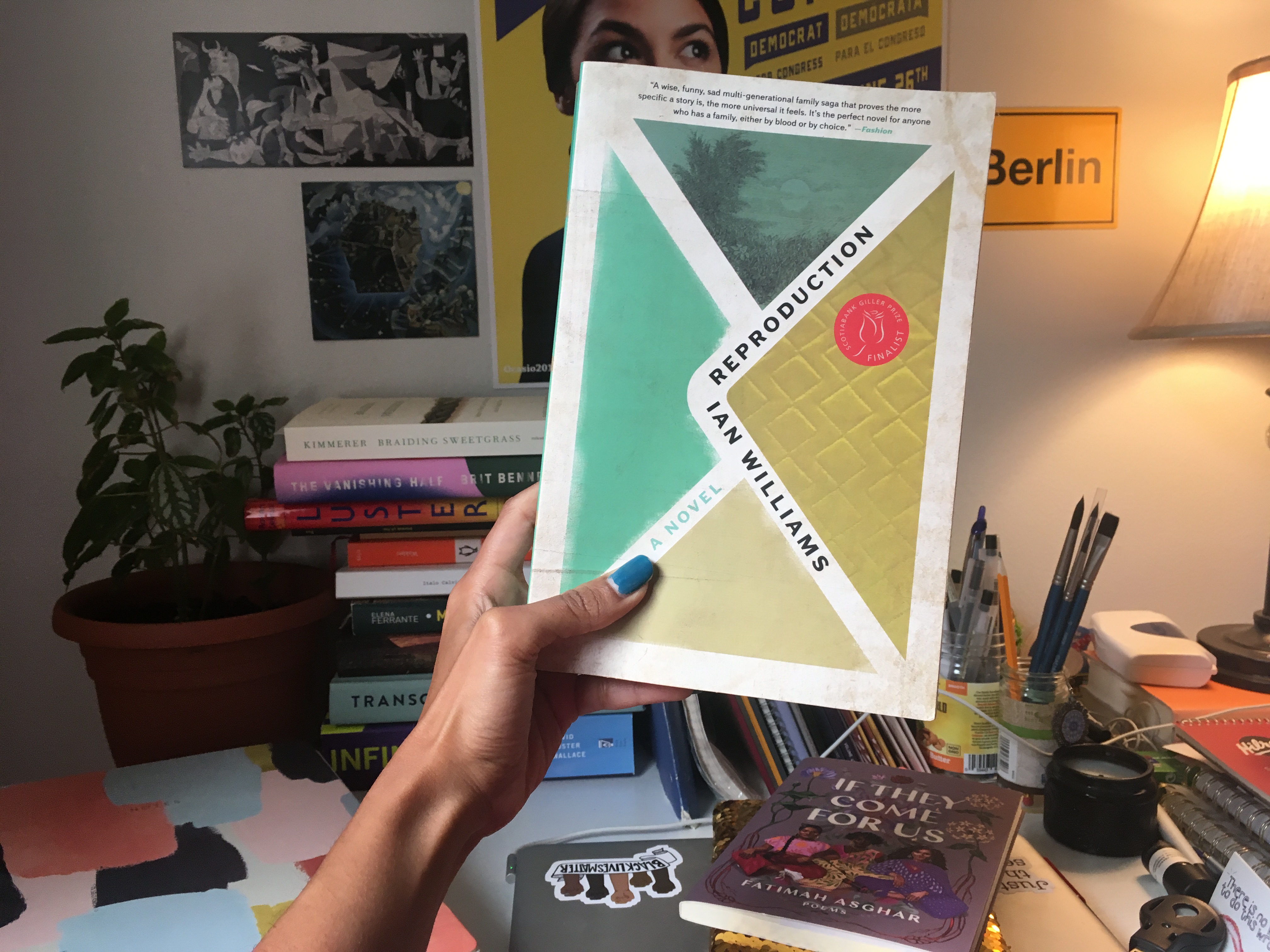

I never understood why critics sometimes describe books as “devastating” but after reading Ian William’s “Reproduction,” I get why. The book is, at once, inspiring and discouraging. It’s inspiring in that it shows you what language, story and poetry are capable of. It shows you how intelligent and multi-layered narration can be. It trusts you and makes you feel smart. And then it’s discouraging because it reminds you that you could never write anything remotely like this. Anything this masterful and intricate, this rich, and at once, joyfully airy. Like, why bother, you know? But good god, it sure does make you want to try and swim in its wake.

I read “Reproduction” at the very beginning of the pandemic that swallowed us whole like a superstar. It feels like I read it in a different life, in a different world. I had watched clips on Twitter of Ian accepting the highest literary honour in Canada, the Giller Prize for Fiction. To be sitting across from him now in a restaurant on Main Street is surreal. I can’t believe that people let me do this.

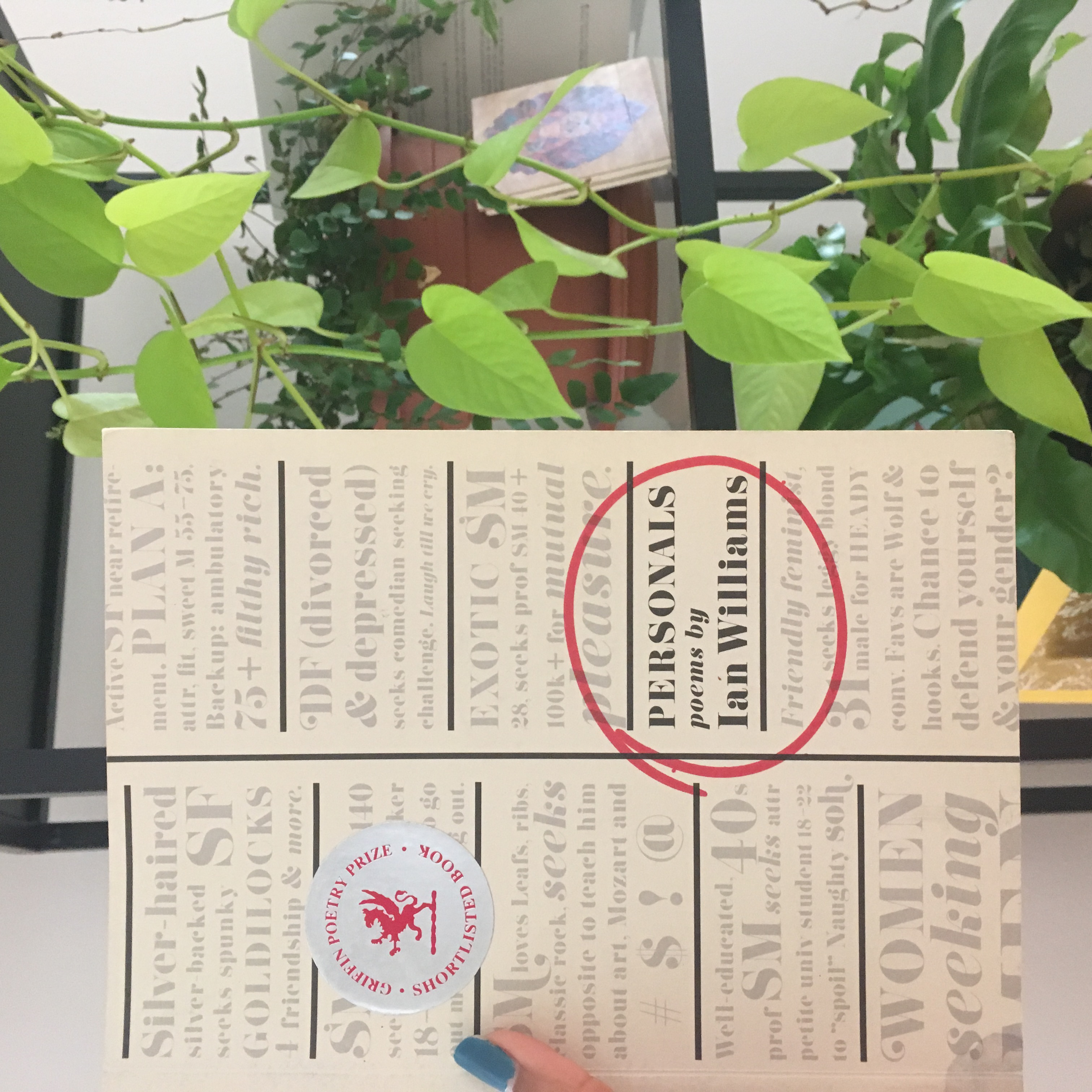

When Ian won the Giller, the #Canlit community was elated and for writers and artists of colour, the moment was personal. Although the prize has been regularly awarded to writers of colour like Esi Edugyan, M. G. Vassanji, Madeleine Thien, Michael Ondaatje, Rohinton Mistry, Vincent Lam and Andre Alexis, the Canadian publishing world remains highly homogenous. For Ian, this award has been long in the making. His first collection of poetry, “You Know Who You Are,” was shortlisted for the ReLit Awards in 2010, his second collection of poetry, “Personals,” was shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize and Robert Kroetsch Poetry Book Award in 2012, and his first collection of short stories “Not Anyone’s Anything” won the Danuta Gleed Literary Award in 2011. Winning the Giller Prize feels nothing short of a dream for Ian. A sci-fi dream probably, with the confounding veneer of a pandemic that cut short the Giller Prize’s usual international programming.

“Well, winning the Giller prize was predictably amazing,” Ian confirms, “but one of the best parts was spending time with the people on the list with me- Alix, David, Megan, Michael and Steven. For a few months afterwards I was flying all over the place and then Covid-19 happened. It disrupted all of our routines and rhythms. I’m trying to find ways to still be present through it. Mostly in front of a screen. I mean, that’s tricky, right? Something is lost once you’re not in the same room as people. The transmission of energy gets diluted.”

The lockdown has forced us to make a mounting series of personal and professional negotiations with the world. We’ve gradually grown used to losing everyday conveniences that had previously been invisible to us. Walks have had a major cultural moment. Through this steady acceptance of losses and rediscoveries, however, has emerged, a bright space for stillness, quiet, rest, and most importantly, for time. “The thing is,” explains Ian, “I was already very tired in March! I needed time to work and write so Covid-19 was actually a bit of a reprieve. I’ve been really excited about the things I’ve been working on through it.”

#plotcharacterssetting

“Reproduction” is Ian’s debut novel. It is a 400-paged saturated read and took him seven years to write. In press it is usually described as being a story about strangers becoming family but I find that classification to be reductive. Edgar, a wealthy older white man meets Felicia, a teenager from the Caribbean, when they both visit their ailing mothers in a Toronto hospital. Grief forges a bond between them. It grows like a garden and extends outside of them. They separate and Felicia gives birth to Edgar’s son, Army. Together the young mother and son live in their Portuguese landlord, Oliver’s basement suite in the suburbs. We meet Oliver’s daughter Heather who Army is infatuated with and her little brother. New relationships are formed and solidify into unexpected familial ties.

“Reproduction” is set mostly in Brampton where Ian himself grew up. Brampton also happens to be where I saw him read at the Fold Festival in the fall of 2018 with Esi Edugyan, Whitney French, Cecil Foster and Natasha Henry. I tell him about how during the Q&A period the only white man in the room stepped up to ask a question. We all rolled our eyes but then Ian broke into his signature big smile and told everyone that it was his high school English teacher, upon which everyone backtracked with enthusiasm and aww-ed collectively. Afterwards, my partner and I drove to one of the 4-Google starred Indian restaurants nearby and ate hot samosas before heading back on the ruthless 410 and 401 to Toronto. The book reads like a love letter to these suburbs and their organic and deep-rooted multiculturality, something Ian very much intended. “Brampton can hold a story on its own,” he affirms. “I wanted to give it its rightful place not outsource the story to Toronto. It’s funny how people write about cities or the country and farms. But the in-between space where many of us grow up gets neglected. I wanted to do justice to the experiences of people who grew up in the suburbs.”

The best part of Ian’s storytelling is the poetry and experimentation of language with which he infuses pretty much every sentence. Every sentence, in Molly from Insecure’s words, does the most. Ian is never satisfied with a regular sentence and because of this, ”Reproduction” is rewarding on a micro-level as well as a macro one. The book explores multiple themes: love, parenting, race, class, and death to name a few. Many of these are pretty dark, but you don’t come away from “Reproduction” drained. You come away instead marvelling at the beauty and acrobatics of Ian’s language, as well as with a deep connection to his intricately fleshed out characters.

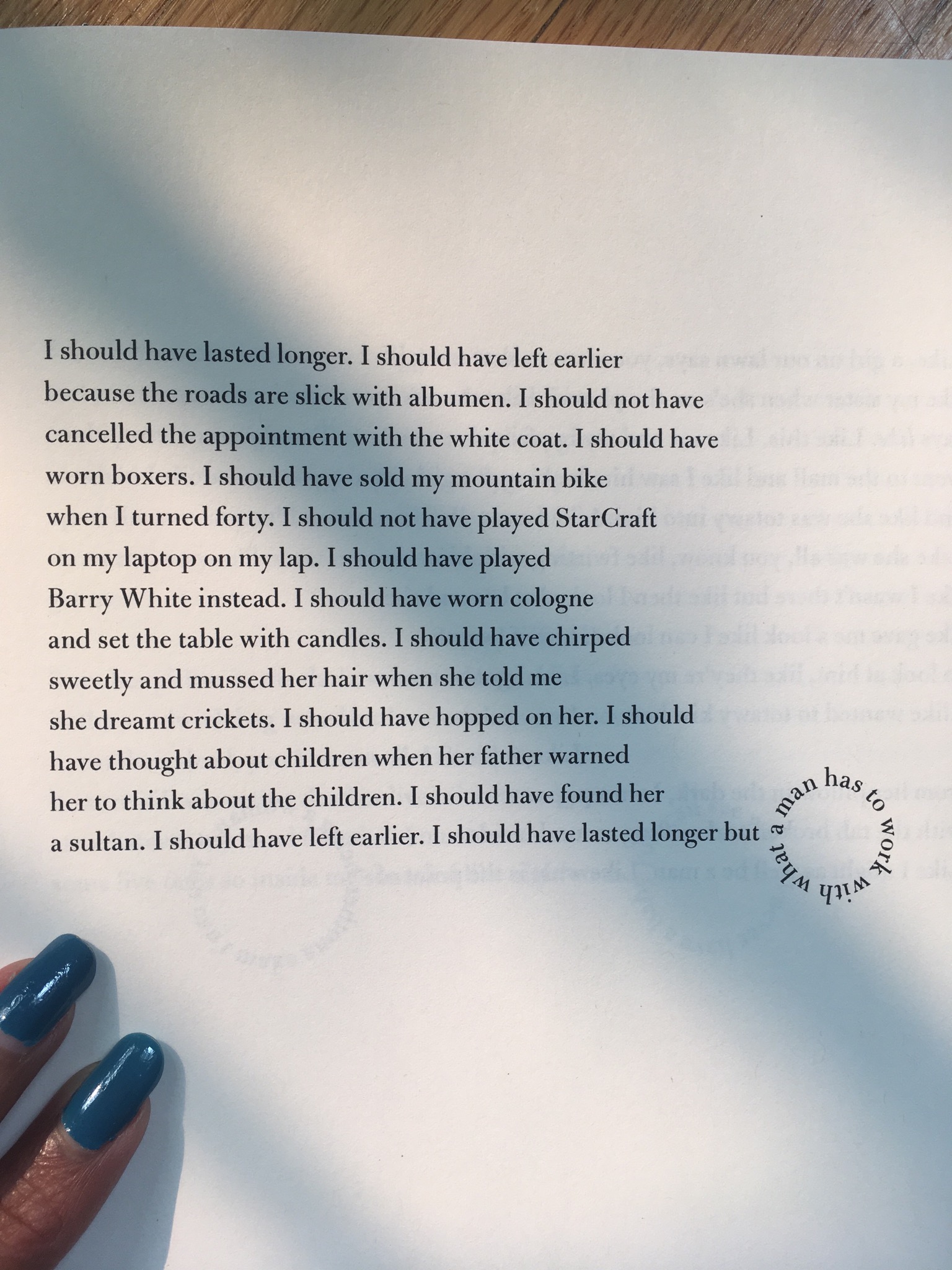

For Ian, “Reproduction” was the next step in his quest to understand how we form bonds as humans. “I’ve been really fascinated by human connections. That’s why Covid has been conceptually intriguing for me. The book I wrote before this, ‘Personals,’ is a collection of love poems about people trying to connect across digital landscapes but ultimately failing. I was in my mid-thirties when I wrote it. I was not married, I didn’t have kids and yet I found this compulsion around the subject of having children as a man. A lot of my female friends were experiencing a similar kind of thing. At the time of ‘Reproduction’ I was thinking about children again and how humans perpetuate ideas and then perpetuate themselves. I was thinking about the things we come pre-programmed with and the things we absorb from our culture and our societies. There was also the writing challenge of it. Could I do a full-length novel? Could I make a book reproduce itself? And how so?”

#theproductionofReproduction

Writing the book over seven years was an intensive draft-driven process. Ian lets me in generously on it. I feel incredibly lucky. He says the concept of the book was clear to him but it still took a long time to write. “The book went through twelve drafts and these were multi part drafts, like 12a, 12b, 12c, 12d. There was a part in the middle where I cut the story in two and had to discard half of it. It just wasn’t working. I had to throw out 25,000 words and rewrite Part 4. Those are the kinds of things that I find really devastating. You put all this work in and then have to let it go. It’s necessary but it feels like wasted work.” He asks me if I’ve made big cuts to things. From my baby writer’s standpoint I can’t really say that I have. But I’ve had many white editors cut down the beating racialised hearts of my journalism pieces so I am familiar with the pain. Additionally, as emerging writers in my writing program, letting go of writing that doesn’t serve us and sifting through feedback to take only what will, has been quite the lesson.

“You want to make it work, right? You want to salvage it. I could justify the reasons for that one part being there. I had been doing it for months. Eventually I got the courage and the clarity to say, no, this just has to go. I’ve tried it enough. When you work something too much it’s not supple and flexible anymore. It’s a little destroyed. I tried fixing things too much and just needed to sweep it away. The book changed a lot.” When it came to characters, Ian says that Felicia was hard to write because she was very inward looking while her son, Army, was the clearest character he has ever written. “The story starts before Army but it comes alive when he enters it. Even before his birth you hear him popping up in parentheses, ‘Hey pretty lady’, that kind of thing. He has momentum and optimism. He keeps the book alive. Army’s presence in the book said to me: I want to live, I want to exist, and you’ve got to make this work out for me! I have great fondness for him.”

Ian famously did not show the manuscript to anyone but his publisher and his agent, and that too at much later stages. His editor came into the picture at Draft 10. “I feel like the work is not worth sharing until I’ve executed the thing that I set out to do. I know what I want to do, I know what I want to achieve, and I have a vision for the project. It’s not something I recommend for everybody and it’s not the way I’ve always worked but it’s the way that’s worked for me since my early thirties onwards. Something shifted then. Early on you need the feedback of other people. You need validation and encouragement. But for this project, the validation and encouragement came from within the project itself. I’d wake up, reach for the manuscript and feel like, ok, I don’t need anybody yet because the guys in here all need me.”

Writing a 400-page book is the ultimate project management job. It’s a marathon and not a sprint. “Draft 6 is when you want to die,” says Ian, “Draft 4 is when you’re cutting parts out of the story. Each draft has a specific function. There’s a draft for point of view, one for character, one for setting, one for description, one for dialogue. Otherwise, with a story of that scale, you never have the focus as you’re revising. I’m a fan of targeted and specific drafts. Don’t worry about the characters if you’re only interested in the plot right now. Don’t worry about the language yet. That’s a late draft for me.“

With these revelations, Ian demystifies what is simultaneously the biggest nightmare and the biggest dream of every emerging writer – to finish or even visualise a finished product. My conversations with Ian about craft will stay with me for a very long time. I’d interviewed writers in the past but none had let me in so transparently. Perhaps it was because I was asking the right questions about craft, having entered the world of writing a little more officially through a writing program. But I also think it has a lot to do with the kind of writer and teacher Ian is.

#academia

Ian is currently teaching Creative Writing at UBC and has had a long teaching career in Canada and the United States. He has a Ph.D. in English Literature from the University of Toronto. His research focus there played a big role, I come to find, in writing the characters of “Reproduction.” “I learned to write from reading canonical texts, all of them white, most of them male. The education I had was an education of loneliness and desperation because there wasn’t a space at the University of Toronto to write expressively. My Ph.D. research though was very useful to me in writing. It was about voice and tone. It asked how we identify a speaker when the page claims to be neutral and claims to erase markers of identity.”

“The project examined markers in narrative that we can identify as feminine or Black or straight. What remnants of the body are left behind on the page? Is it in the way we use our sentences or our words? The project helped me understand how voice behaves and works in a way that I deploy in my writing. I understand how to create a voice that sounds female or that sounds young more accurately because of it.” Ian’s deep understanding of the textual markers of gender, class, age and race allow him to recreate, and authentically at that, any character he wants to represent.

“In the end, I discovered that it’s mostly a two-way dialogue that happens between the reader and the author, where the author is playing into the reader’s expectations and stereotypes of what, for example, a Black voice ought to sound like. So it becomes about courting some of those stereotypes and resisting others. The reader then sees a Black voice expanding and says, oh Black voices sound like this and this and this and also this! There’s this dialectic that moves back and forth where we work with stereotype to dismantle it and present a fresh and authentic voice. This fresh voice then becomes codified, and we destroy it again. So on and so forth. It’s an ever-evolving process of representation.“

#outlining

Ian’s approach to outlining bigger works is an eye opener for me. There are a million ways to skin a cat. Everyone has their own way of getting thoughts on to the page and then another for rewriting and editing. The overarching method that is most popular in my program is the “vomit” method. It’s as delectable as it sounds and significantly less torturous than measuring every word in your head and transferring it on to paper with crystalline perfection. You just let everything out first and deal with it all in the editing phase. I’ve got that down but envisioning anything beyond a short piece still gets me sweating.

In class we’ve come across quite a few approaches and tools but Ian’s method is by far the most freeing and intuitive. “First couple of drafts are all about the messy plot. Just getting it out. But there comes a point where I take large pieces of paper to the wall and start mapping things,” he says. “UBC Creative Writing is big on outlining for writing fiction. I can see the value in it. It saves you a lot of time in the end. But I prefer to do a mid-project outline. I think of it as an inventory rather than an outline.

“After I’ve written everything, I map every scene on paper and see what’s there. I work from a place of where things already exist rather than where things have just been imagined. With an outline I find that I’m squeezing people into a story or a plot and making them do things. What I do instead is write first and afterwards assess what’s there around Draft 4 or so. Then I haven’t forced anyone to do anything they didn’t want to do. The story has emerged organically from these people’s lives and now, let me see how I need to order this so that I can amplify certain effects. The detailed charting happens after I know everything that’s there. It happens more from a desire to synthesize and organise rather than a desire to create.”

#constantevolution

I ask if Ian has changed a lot as a writer over the years. He says the first books of every genre were the most difficult for him. The first collection of poems more difficult than the second and so on. But “Reproduction” had its own challenges as Ian’s first novel. With it he had to figure out the genre of fiction, how it works, including how pacing works. It was a technical challenge in terms of size and word count too. “I want to resist the idea of saying one was more difficult than another because that implies that the more difficult thing is the better or more rewarding one. I think they just behave differently. I have certain muscles that are well attuned to poetry that don’t work in fiction. So I needed to develop other muscles to write fiction. When I went back to writing poetry, after “Reproduction”, I found certain things about poetry to be difficult again.”

It’s clear from Ian’s works that pushing the envelope of form brings him great joy and he always has a lot of fun with it. “Experimenting with form is a way for me to do a couple of things,” he explains, “1. it keeps a contemporary reader interested, 2. it respects the intelligence of a reader, and 3. it evolves the form of the genre. As a writer, I want to retrain how we approach a book and the way that a story unfolds. I think readers can handle disjointed, complex and interrupted stories. My exploration involves looking at what else is possible in a form that people think is conservative, conventional, closed and fixed.”

#theidealandnonidealreader

Ian asks me what I find most difficult about writing. I tell him I find it challenging to focus my attention on the reader. I find it challenging to take them through a story and make sure they see what I see. “When I’m writing for the wrong reader I get tied up with that problem too,” he commiserates. “I’m writing a secret project right now and in it the orientation I take is determined by the reader. Change the reader when you’re writing fiction. Pick whomever is the ideal reader for you. Someone non-judgemental and who doesn’t care too much about whether you get it right. And someone patient who lets you tell the story at your own telling and your own pace. What does that person want? It’s not excitement necessarily. It’s not a beautiful phrase. Maybe it is that they wanted to be seen and well represented. Nobody has ever said the word “magga” in a poem before which is a word that my family grew up saying in Trinidad. Maybe this poem is for people who’ve never seen that word written anywhere.”

I tell Ian about how my writing has changed since I started writing for workshop groups. I started censoring my writing because I thought they would be “too much”. Especially since my workshop group was mostly white. We talk about the challenges of being writers of colour in the context of all white workshops. What it’s like dealing with microaggressions subtler than the down on your arms. I tell him about stories being written by white writers about people of colour in our year. The topic is hot. As I write this, we’re just coming off of the heels of the “American Dirt” saga, the freshly dropped Jessica Krug story, and our very own Canadian, Gwen Benaway episode. We seem to be having a global reckoning through which people of colour are learning, alongside white folks, what is acceptable and what is normalised violence.

“My question for those writers would be: why do they feel the need to be in spaces that are not theirs? Especially when there are other people who could do it and are doing it. What is it that they feel they can do better than these other people? What is this great hubris? Or ego that makes them think that they can do it better? That’s my question. My intent is not to be hostile in a workshop but to genuinely understand that. The flip side of that question to those people would be: what is it about your story and your background that bores you or that you think is beneath consideration? These writers are reaching for the exotic or making something exotic and then repurposing it for their own artistic desires. There are some really tangled issues at the base of a project like that.”

#toworkshopornottoworkshop

There has always been a debate about the effectiveness of writing programs and workshopping. Stephen King in his memoir, “On Writing”, famously declared that he was not a fan of either, preferring instead to use all his time producing work and trusting in the practice to become a better writer. Workshopping can even be a negative experience and stifle unique voices. Ian tells me about the importance of having a writing community but more for the purposes of camaraderie and less for critiquing. He meets his weekly writing group on Main Street, which includes his friend and my TWS Mentor, Kevin Chong. He writes with the group but doesn’t share his work with anyone. “We’re all in our own projects but we’re still somehow together. I think that’s important for writers. You can see someone across the table who is engaged in your struggle and shares similar challenges.”

For new writers workshopping is much needed for understanding the minds of their readers. But once you’ve ironed out those initial kinks, Ian says, critique does little. “By then you’ve internalised enough of those voices that you can play their roles. You can play the really authoritative person in your workshop and the nervous person. You absorb them all. That’s not the hard part. Criticism has never been the hard part of writing. Writers are inherently critical of themselves and their work. What’s important in a workshop is the communal experience. The support and the encouragement are more important than precise feedback.”

Writing programs and especially workshopping environments have been notorious hotbeds for microaggressions for writers of colour. In Junot Diaz’s article titled “MFA or POC” he talks about being approached by a constant stream of students who shared experiences along similar lines. He details instances in which white writers constantly write about people of colour and harshly critique and misunderstand the works of writers of colour. It doesn’t help that MFAs are expensive and need connections. Both hurdles that are more likely than not a problem for their largely white students.

“It’s so hard to assess. When it comes to feedback, often times there’s a point that the person is making that’s valid. For example, if someone says to me ‘I never understand why people in your stories are so respectful of their parents. If your character doesn’t want to do that she can just leave, right?’ What’s valid there is that person has identified a pattern in my stories. What’s not constructive is calling into questions the values of my culture compared to the values of western culture. My intention was simply to put forward how things are in my world, not to have it interrogated or belittled. That ‘what do I take’ and ‘what do I throw’ choice is important.

“If that doesn’t happen we end up being silenced and writing to please our critic. We end up with stories where characters behave as they ought to, as readers expect them to behave, and those are really dull, lifeless stories. A little pushback is necessary. My hope is that white writers recognise the supremacist action of interrogating the ethos of the stories of writers of colour.” Part of the solution is also about building your confidence as a writer so you know what will serve you and what won’t. “And you don’t have to go into a defensive mode,” adds Ian, “it somehow always becomes the fault of the racialised person in workshops of being unclear, of being exotic, of being difficult.“

#canlitsowhite

To exist in Canadian literary spaces, in publishing and in academia, as well as in the art and media worlds in general, is a strange experience for writers who identify as Black, Indigenous, people of colour and LGBTQ+. We haven’t existed in literary works outside of the white gaze until this century. We’ve always been here but our voices have never been front and centre. We were written about but never had the chance to tell our own stories. This explains the current state of writing spaces and their growing pains. Today’s writing spaces are “not used to” writers of colour. They are spaces that were designed to stay white and oust anything that challenged their status quo. These spaces crave new ideas and voices that writers of colour bring but are not equipped to protect the writers from the invisible white supremacist aggressions woven into the system.

For many writers to read work by non-white writers is a recent phenomenon. One thing I have noted in works of writers of colour is their affinity and inclusion of pop culture. I find that to be true about Ian’s narration in “Reproduction”. His prose is elegant and elevated, but he also includes healthy portions of slang, pop culture references and vernacular. I find this marriage of “high” and “low” art fascinating. It also begs the question: who decides what “high” and “low” are, especially when “high” is attached to work made by white male artists and “low” is assigned to work made by women and marginalised folks. It’s why Taylor Swift is not considered high art and slam poetry is not considered poetry.

“That’s right. It depends on who’s making the art. Folks expect a certain self-awareness and self-critical behaviour from people of colour that they don’t expect of white folks. The assumption with white folks is that they know what they’re doing when they produce art. Spontaneous art made by white artists is seen as deliberate and planned, but with artists of colour, it is accidental, it’s ‘I’m not sure he knows what he’s doing’. There’s a reading of our intentions and assumptions made about our capabilities.” I bring up one of my favourite shows, The Mindy Project, which like Ian’s work, is saturated with pop culture references. I’ve always wondered why that is because pop culture is also something that I feel drawn to include in my own writing. “Pop culture is a place where folks are used to seeing people of colour,” says Ian, “so we’ve got these common shared representations of ourselves that we can then as writers, deploy, manipulate and correct as necessary.“

Ian works in elements of pop culture seamlessly into his storytelling. As an Old, I already find myself teetering when talking about TikTok houses but Ian’s writing never feels out of touch. It doesn’t feel like it’s trying hard to be cool. It just is, especially when he writes young characters like Heather and Army. Turns out Ian finds writing about pop culture to not only be a fun exercise but a writing challenge and a necessary injection to keep readers guessing and entertained. “I think when things stay in one mode for the entire duration of the project they become dull. When you stay in that high art mode it’s exclusionary. You’re saying that things that belong in high art are these kinds of sentences, this kind of tone, these kinds of references. When you stay in an overly popular mode where it’s all text messages, Twitter back and forth and Snapchat, it’s all buzzy and contemporary. But if you do that too much you’re also showing disregard for the tradition that made the novel possible. Just like we undulate in real life between different ways of being, a book also undulates through different ways of knowing and representing. I don’t want to constrain a book to remain only in that one mode of high art or low. There’s a dignity that comes from high art and there’s a pleasure and recognisability that comes from the popular, contemporary art. To have them meet in one place is a communal endeavour. Imagine them both attached to people and then bringing those people together. People who talk Picasso and people who talk Fifty Shades Freed in the same room. Building something that they both like is the pleasure of writing a novel.”

Ian feels the same way about humour, which is also omnipresent in “Reproduction”. For a book that starts and **SPOILER ALERT** ends with death it never drags you down. It stays light on its feet and is always radiating hope. Ian believes that’s a reflection of his worldview and personality. He also thinks that you can’t decide to write funny and then be funny. “I think it comes from how one engages with reality. If you’re inclined to view the world ironically or inclined to see the lighter side of things to cope with a pretty dark world, then the story gets structured with a worldview that is not altogether bleak. There’s also a distance and lightness of touch that makes the writing readable. At the end of the day, you want to turn the page and feel there’s something hopeful just around the corner.”

#writinginthetimeofcapitalism

We move on to talk about how strange writing has been during the pandemic. With our concentrations deteriorating from a perpetual state of anxiety about the future, productivity has seen better days. Being confined within four walls up until much recently, has been tough on the creative soul that seeks regeneration through socialising and travel. Ian’s process however has changed little after the pandemic. Now with restrictions on travel he gets to dive even deeper into his work. “I work a lot. All I do is work. I’m out of balance!” he says, “my writing process is just writing all the time, especially when I’m in the grip of a project like the one I’m in right now.” He admits that he slept for four hours last night, had twelve crackers and went back to writing afterwards. “I realise there’s a window that I need to be present for to write. If I’m present for the month (I’m giving myself a month for this one) and I cooperate for a month with it, then that will be a year’s worth of work in a month. That’s going to mean eating no breakfast and not getting a lot of sleep for a while. But in the end it’s worth it to me. For some writers the balance is more important. But I need to cooperate with the energy of a project and my own motivation and desire. There will come a point in the project when I don’t even want to look at it. Buy right now I’m not in that phase so I’m going to give all of myself to it. My process is to yield to the work.”

We talk about work-life balance, that dreaded, mythical Holy Grail that we’re always promised but can never seem to nail down. Ian admits there’s a cost to his writing process. “I turned 41 last month. I’m not married and I have no kids. I’ve got a great career, and a great job and a lot of writing success. But my relationships probably need a lot of work. And my friendships too. I disappear for months at a time. My friends are kind enough to understand that that’s not for lack of caring; it’s just how I function and what I need in the world. Those are trade-offs that not all people are prepared to make. Nor should they have to,” he emphasises. “I think it’s unreasonable to ask writers to be slaves to their work. It’s one thing when you’re voluntarily sacrificing yourself to your work but to be bound by some romantic societal expectation that writers work in a certain kind of way and suffer by not marrying and not doing anything else is dangerous.“

This hits close to home for me. The struggle of choosing capitalist existence over my artistic aspirations, only to have them tug at my heart all day, is one I have yet to overcome. I tell Ian about the pressures of having traditional careers in immigrant families. Capitalism is so integral to immigrant families that it has become entrenched in our cultures. The celebration of wealth and professions that lead to it: finance, engineering, medicine, and business, and the relegation of anything to do with the arts has been a tough pill to swallow. My parents and I went through this whole discovery together. My father, you could safely call him a Boomer, was an engineer who loved his job. It allowed him to raise a family and take it with him all over the world. It was chill enough for him to be a full on activist on evenings and weekends, organising for anti-caste initiatives in India from abroad. For him a job provided the freedom to do what he loved and give back to the world.

But the world has done a 180 for my generation. Now jobs consume you and expect full allegiance. You’d be lucky to have time for family, cooking meals or exercising. All this is to just keep a job, excelling takes even greater personal investment, if there is any left to begin with. A Bachelors degree no longer guarantees an entry-level job. Those who insinuate that oat-milk-loving millennials are lazy wouldn’t stand a chance in the current brutal economical circumstances. This economy makes it impossible to wait tables three days a week and write a book in the remaining four, the way writers used to be able to do. Becoming a writer is becoming a harder and harder dream. Add to this harsh financial reality, the barriers of racism, sexism, and homophobia.

Ian’s path to writing emerged through academia but it still required taking risks and going against the grain. “It’s very tricky because the security that our parents want for us is understandable seeing where they came from and all the material comforts that they want to protect us with. They believe they’ve saved us from some things, which is poverty, uncertainty and precarious work in this world. But they’ve also imprisoned us in structures of achievement, moneymaking and capitalism. I did start school wanting to be a writer but it was not a viable career for me at all. The only way I could do it was with the same single-focus devotion that I could bring to my academic life. That meant working a job as an academic in the day and waking up in the early mornings to write. They seem like related activities but they, in fact, make very different demands of you. The writing can easily take a back seat because there’s no one reinforcing it. You could almost work more. You could be better and better at your job.”

When you come to think of it, being a writer is a strange, strange endeavour. And yet so many of us can’t turn away from it to choose logical and practical lives instead. “Writing is seen as a hobby and no one values it. It’s bizarre that we’re even in this,” reflects Ian, “imagine being discouraged on every front for the thing that you really want to do and still pursuing it nevertheless. At some point you’d think that people would wake up to the fact that this is actually really important.” He mentions how the avenues for becoming a writer have little to do with writing like industry memberships and academic connections. Add to this the struggles that you face as an outsider, especially as a Black, Indigenous and person of colour. It’s a wonder that writers, especially writers of colour, keep writing.

#Blacklivesmatter

Canlit, as the Canadian publishing world is affectionately known, has been under scrutiny for its cliquey nature for quite some time but questions about its exclusivity have become more urgent with the Black Lives Matter movement gaining momentum in the spring. Suddenly Black Canadian writers, including Ian, have been expected to weigh in on racism and discrimination in Canada. Desmond Cole’s non-fiction slash memoir “The Skin We’re In” is flying off the shelves and nine out of ten of the books on the non-fiction charts for most of the summer were written by writers of colour. All the major corporations have been posting black squares on Instagram. It seems like white folks are finally ready to talk about something they had created a long time ago but now no longer understand – race. Much of the labour of this education and problem solving, however, has, and not surprisingly, fallen onto people of colour. “I hope that there is true systemic change that makes publication and platform possible for people of colour. I don’t think that we need to beg for it. There are lots of people of colour that are qualified and bright and who have been underutilised in their places of work. It’s about taking a step back and realising that the people you need are probably already in your environment or close. I was going to say why not give them a chance, but that implies that they need to prove themselves. They should be entitled to that opportunity to fulfil the thing they are capable of doing just like everyone else.

I’m not an expert in Blackness any more than I am in whiteness. But people of colour do bring the dimension of knowing another reality that white folks generally don’t. We don’t just bring one point of view. We bring the norm and then we bring a bonus.”

I tell Ian about the BIPOC Writers Circle we’ve come together to create in my writing program and how helpful it has been to have a space to openly and honestly process the events of the summer with Covid-19 disproportionately affecting marginalised communities and police brutality on full display. We’ve been able to find a space to talk about some of the abhorrently racist pieces we’ve had to workshop and the ignorant comments we’ve had to field about our own works. We’ve been able to write a few letters of concern to the program’s administrative team and devise a list of improvements for the program. All of this is free labour. “That’s work that you’re doing that your white colleague doesn’t need to do or won’t do,” points out Ian, “that’s work on top of the writing of stories that you’re doing. Writing is work that has an extra valence to it. It’s not just skill-based work. It’s work that carries with it repercussions for how we live.”

I ask Ian if he is expected to write about race all the time and especially now when race is “trending.” It must get exhausting to talk about trauma and just plain boring to spend so much time on one thing. Having Black writers weigh in on conversations about racism in Canada any time a Black life is violently lost and then not making any meaningful changes to prevent future tragedies seems like a royal waste of their time. How many times will we be having these conversations? “I do find it exhausting to pretty much have the same conversation multiple times,” says Ian, “the conversation more or less, to strip it of niceties and politeness, goes: so, what does it feel like to be killed… again? And what should we do about killing Black people? The conversation that I would like to see, and not necessarily be a part of, is to ask white folks: what does it feel like to kill people, again and again and again? Why do you keep doing it? That’s a conversation that takes the onus and the responsibility off of Black folks and onto the people perpetrating the crime. For instance your writing program could stop asking writers of colour to solve the problem and instead ask white writers: why do you keep saying these stupid things to people of colour when you realise how hurtful they are? Why do you keep doing it? That’s a conversation that I’d like to see.”

#sunnyskiesahead

Fortunately for all of us in the writing communities, the new generation of writers is less hung up on asking for what is realistic. They are tired of systemic racism. They don’t have time for anti-Black racism, sexism, transphobia, homophobia and colonisation. They want radical reformation to combat climate change. They’ve taught the generations before them by showing up in the streets, for months on end, sometimes every day, how powerful hope and optimism can be. They’ve proved that speaking up is not just an empty gesture but can lead to actionable change. For those young writers Ian’s advice is spot on. “People are your biggest resource. It’s not even programs or degrees or credentials or any of that. It’s the people within programs and communities that you meet. Find those people. If you’re in a writing program, spend it to develop your craft but also find people that you want to take with you for your life. For 10 or 15 years. If you can find one or two of those people, that’s worth more than anything else. Find the people who get you and to whom you don’t have to justify your experience. You’ll find that brilliantly together you will start rising to the top. It’s miraculous how it happens. It’s not a solo climb. Energy passes between you.”

I ask Ian what comes after “Reproduction” and he tells me he’s working on a poetry collection called “Word Problems” that should be out soon. The collection rethinks what a poem can do in terms of activism. His next novel is called “Disappointment.” And then he tells me he’s working on a top-secret project which is absolutely fantastic. Of course now I’m on an impossible cliffhanger. As we conclude our conversation and walk out of our Main Street restaurant, Ian remarks, “just doing my usual scan of the room to see if I’m the only Black person in the room.” I nod with familiarity. “That’s the Vancouver experience!” I offer, “I’m very often the only brown person in these parts.” We laugh but at least we’re able to walk away knowing that the world is on the precipice of some big changes. Because now it seems to be really listening and Ian’s definitely got its good ear.

Get Ian Williams’ work, including “Word Problems” out now, at the Indigenous-owned Vancouver bookstore, Massy Books, or at your favourite bookstore. And catch him at the Vancouver Writers Festival.

– Prachi Kamble